yang ‘tu yang ‘ni: Ways of Seeing and Reading Ismail Hashim’s Photographs

I. Introducing yang ‘tu yang ‘ni

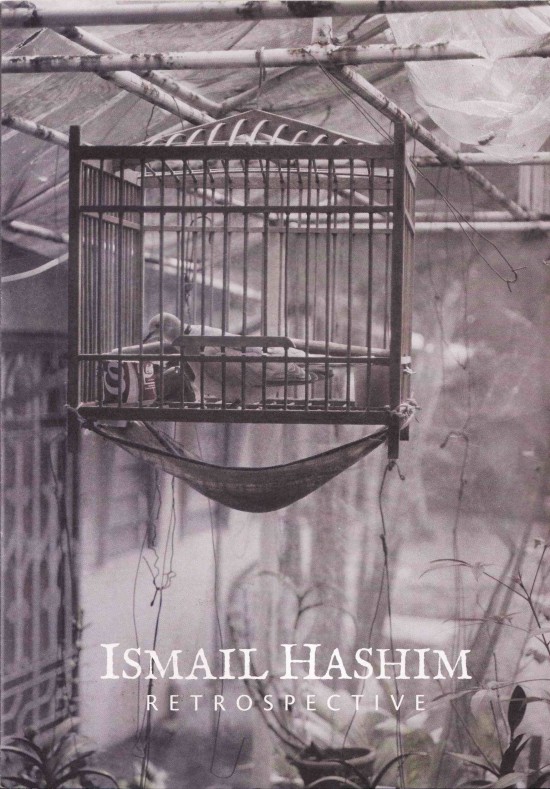

Flyer for Ismail Hashim Retrospective at Penang State Art Gallery, 2 – 30 Nov 2010 (source)

Very little has been written on the photographer Ismail Hashim and his work. The few writings that exist are short descriptions by various writers which can be grouped into a few broad areas [1]:

1. Ismail is a “social commentator” with a strong sense of “social justice”. He “exposes” Malaysia’s “social milieu of a multiethnic population” in attempts “to surmount ethnicity”. The themes include “children, the environment, peace, unity”.

2. He retrieves the “evanescent” and “hidden aspects of Malaysian life”: its “vanishing scenes” and “hidden beauty”. His works are “an ode to the forgotten”.

3. His photographs belong to “new realist modes of perception”. He “record[s]…things as they are” “without idealizing its subject-matter”, thus their “unstagedness”.

4. His photographs cull the “uniqueness of everyday life”, “ordinary life”, “things common” and “turns [sic] the blandness of the ordinary visual environment into something that demands not to be taken for granted”.

5. Other less recurring observations include: his works “evoke a sense of time and space” and are “infused with humour and wit”.

These observations, even while anecdotal, become crucial clues to lead us into more complex levels of seeing, experiencing, reading and interpreting Ismail Hashim’s photographs. They constitute the outer layers – the skins, so to speak – that invite and require peeling in order to fathom the nuances and interconnectedness of other layers beneath.

The most useful entry-point would be the title Ismail Hashim provided for his own solo-exhibition two years ago: yang ‘tu yang ni (literally translated as “this ‘n that”). The reason the title is so informative lies in the artist’s own interest in linguistics and his oftentimes sophisticated punning and play with the Malay language, especially northern Malay loghat (dialect) and the English language. Ismail was a teacher for deaf/hearing-impaired children for some years in the 1970s, hence, he is extremely at ease with language as representational and performative actions as well in what he calls “reading and residual hearing” and “total communication.” [2]

The word yang has various meanings and uses that are relevant to the discussion I will pursue. Yang is a penyambung (ligature/connecting article) used to connect parts of sentences and introduce attributes; it functions as a modifier of the subject/object; it also relativizes meaning. Yang in this context also behaves as an auxiliary verb of “to be” and “being”, referring to past, present and re-presentational states.[3] All these uses emerge as particularly useful when we consider that much of contemporary discussion of photography has its impulses in the study of phenomenology [4] and semiotics [5].

Returning to examine the title, the choice of the commonly used “yang ’tu yang ‘ni” in colloquial Malay to denote and encapsulate Ismail Hashim’s body of photographic works, begins to take on fascinating meanings. This clause bears uncanny semblance and parallels to the metaphysical notion of time and existence, dasein. [6] Yang conjoins two realms – “yang ‘ni” (being this) refers to something both spatially present as well as is in the temporal present and; “yang ‘tu” (being that) refers to something that has been experienced and has presence in our consciousness but is not necessarily in the temporal present or spatially present. [7]

Located within these two intersecting realms of being is the phenomenon of memory and forgetting, human consciousness and conscience, essences, arrested moments and continuous moments. This essay will take these discursive inbetweenness as well as the anecdotal observations of other writers as points of entry and departure in seeing and reading photography in general, and Ismail Hashim’s photographs in particular.

II. Memory and Forgetting

After having ‘nasi kandar’ with a glass of water, 1991

Ismail Hashim captures and presents his images in various ways. His themes and subjects are varied. Sometimes they appear as single images with post-capturing interventions in the form of tinting. At other times, he physically slices the images and recomposes them as fragments within a frame. Others consist of repetitions of a single subject as variations through real time, stilling the moments into time-based narratives. Whatever approach he takes, all his works have a personal and intimate scale, and together with his often provocative titles, invite close scrutiny. Gleaning through his works covering almost forty years, I have chosen four works, which I believe are most representative of his recurrent interests and themes, to explore, tease apart and propose some ways of seeing and reading them.

Taking one of Ismail Hashim’s single image photographs with few interventions, after having ‘nasi kandar’ with a glass of water (1991), we can begin to read it by using some of the entry-points suggested by other writers. It is a highly-composed picture of a roadside scene either shot at mid-morning or late afternoon judging from the angle of the shadows. It evokes “a sense of time and space”; “record[s]…things as they are”; depicts “ordinary life” and “things common”. It can also be an “ode” to a “vanishing world” of roadside stalls which is slowly turning inside and inward into enclosed and partitioned food courts.

These observations are insufficient if we desire to sink deeper into understanding this photograph. They remain as explications, skimming over the surface. There are other levels at play when approaching this photograph: the first is the world of Ismail Hashim, his choice and relationship to the subject matter and the title he has chosen. The second level is our (the audience’s) relationship to his photograph.

For the first level, we can examine his title: Why does it begin with “after having…”? Why a title referring to a performative action? This roadside scene of table and chairs was obviously present and of a specific location when Ismail Hashim shot the photograph; it refers to a moment of yang ‘ni. He was present there with his camera; the scene was in front of him. However, the image as well as the title “after having…” informs us that for Ismail Hashim, an act of someone eating nasi kandar happened – a non-present or past moment of yang ‘tu – prior to him clicking the shutter. Within this photograph are then the two interconnected realms and moments of yang ‘ni yang ‘tu – a temporal and spatial present and a non-present act of eating that is already gone, but recalled and re-presented as photographic memory. Ismail Hashim is asking the audience to think of this image as an experience rather than an unadulterated objective scene or a “realist modes[sic] of perception”. He is inviting us to imagine an act of someone eating and drinking in the photograph but which we can no longer see. He wants us to think of human experiences and not glass and plate, chairs and table.

The second level is the viewer’s relationship to this image. Standing in front of this photograph we will read it quite differently. First, there is the object of the photograph – the physical presence of yang’ ni that exists in the temporal present. We can tangibly experience this photograph through holding it in our hands or hanging it on a wall. It can be both a visual and tactile experience of here and now. In looking at the image, we draw from our own memory of roadside eating experiences. From our minds are culled personal memories of what these experiences are about. Whether it is nasi kandar or char koey teow or nasi lemak or whether it is located in George Town, Dungun or Kapit does not really matter.

What matters, is that we can recognize our own memories and past experiences of yang ‘tu in relation to what Ismail Hashim has depicted and experienced himself. There can only be this identification if we have similar personal and socio-historical experiences and understanding of the “essence” [8] of what a roadside stall eating experience constitutes. But all these lie in the past and remain only as memories and in fact we are seeing a memory because even the physical setting and actual location of this scene do not exist anymore.

Ismail Hashim also clearly wants the audience to look at the forgotten-ness and empty-ness as intertwined and integral to memory, as clearly, it is never complete. Memory consists not only of what is remembered but of elements forgotten and lost in time. He highlights this in the title with two subjects/objects: “nasi kandar” and “glass of water”. But both the nasi kandar and water have been consumed – eaten, drunk and gone; what remains are the empty plate and glass held tenuously by the flotsams of memory: remembering, forgetting, and yearning.

III. Consciousness & Conscience

Tidur punya ralit, bom meletup pun tak sedar (Sleeping uncontrollably, unconscious of exploding bomb), 1983

In another single image work, Tidur punya ralit, bom meletup pun tak sedar (Sleeping uncontrollably, unconscious of exploding bomb),1983, we are again confronted with a complex title juxtaposed with the image. The title, as in after having nasi kandar with a glass of water, also begins with a verb, tidur (sleeping). It is made more difficult with the word ralit. Ralit is an archaic word which also means sleeping but in an uncontrollable, habitual and almost narcoleptic manner. Here, it is linked immediately to the phenomenological notion of tak sedar (unconscious or unaware). Other than the bomb, there is no mention of the woman, cat and television, all of which are dominant subjects in this photograph. But the bomb has not exploded; it is being lifted precariously to prevent it from exploding.

A rudimentary visual explication of this photograph will be to see Ismail Hashim as a “social commentator” exploring the theme of “environment, [and] peace”, commenting on the dangers of war, reminding the audience to wake up. Because it was photographed almost thirty years ago, it can be seen as a sepia-toned “vanishing scene” documenting “ordinary life” complete with an old standing television. After all, this image is still as ordinary, familiar and understandable: sleeping in front of the television while it is left on with constantly moving images and a cacophony of sounds is something majority of us have experienced.

However, this image draws the viewer in through its complex layering of time: Ismail Hashim was physically present at this scene and location that he captured. The television network was broadcasting news footage of an event which was simultaneous to him clicking his shutter. This event of bomb-removal transmitted in waveforms and electron beams could be happening in real time as well or it could be a recorded event. The bomb itself is from the past; it was dropped at an earlier period. Viewing the photograph now, everything in it merely exists as a debris of memory, an arrested moment of time from over twenty-five years ago, none of which exists now. In this image then, memory funnels from the periphery of the present with woman and cat, through subsequent layers of time, to the furthest point in the past by way of the television and into the image of the bomb.

Another difficult notion that Ismail Hashim introduces in this photograph can be inferred from both the title and subjects in the photograph: the ideas of tidur (sleeping) and tak sedar (unconscious) in symbiosis with the triad of human (the woman), animal (the cat) & man-made (the television) relationships. This interplay of sleep and the unconscious as both idea and image necessarily compel a reading that draws again from phenomenology, psychology and metaphysics, fields of inquiry too abyssal and oceanic to consider in any depth in this essay.

In sleep, one is unaware of the conscious, wakeful world of experience and thought. This means that the sleeping woman is unconscious of her surroundings – the interminable din of the television, the flickering images of the bomb, the cat, the fumes from the burning mosquito coil, etc. In her sleep, she is in an unconscious state of mind, neither thinking nor experiencing. But the cat is also sleeping, also unconscious of its surroundings. Here, Ismail Hashim through the juxtaposition of human, animal and man-made relationships poses provocative questions: Are both woman and the cat just as unconscious? Does the cat have consciousness in the first place?

If we take a materialist argument, humans are differentiated from animals because of consciousness, and this consciousness arises because humans “produce their means of subsistence”. This means that humans, unlike animals, make and produce things for their “material life”, and this production is dependent on the historical and material conditions that they are immersed in and emerge from. [9] Animals then, do not have consciousness as they subsist on the world; they do not possess the means or modes of production. In the context of Ismail Hashim’s photograph, the juxtaposition of woman and cat would mean that the woman possesses a consciousness, but because she is sleeping narcoleptically, she has become tak sedar (unconscious) even with a bom meletup (bomb exploding). Despite having human consciousness, she is oblivious to what is happening in the world. The social commentary, so often alluded to by other writers, would seem to emerge from Ismail Hashim’s concern that humans because they have consciousness must also possess conscience. [10] Otherwise, humans will be no different from animals.

[TO BE CONT’D]

This is Part I of an essay written for a monograph (Penang State Museum & Art Gallery: Penang, 2010) published in conjunction with the Ismail Hisham Retrospective exhibition at Penang State Art Gallery, 2 – 30 Nov 2010. We’ll publish Part II next week.

~

NOTES:

[1] All the quotes are from writers such as Redza Piyadasa, Yeoh Jin Leng, Ooi Kok Chuen, Joceline Tan, etc. and are taken from Ismail Hashim’s yang ‘tu yang ‘ni exhibition catalogue (Galeri Seri Mutiara: Penang, 2008)

[2] These phrases are from conversations with Ismail Hashim. He often reminisces about his background in teaching the hearing-impaired in the 1970s as the best years of his life.

[3] The analysis of the headless clause yang ‘tu yang ‘ni are my own. Ismail Hashim used it without caps, and in so doing, it assumes the form of a passing comment and it flattens hierarchies. Commonly used to refer to “this and that” in a literal way, in linguistic terms, the word “yang” is one of the most studied and used articles in the Malay language. It is often merely used as a penyambung (a connecting article) of parts of sentences as in Buku yang merah (The book that is red.) In this particular sentence, it is a ligature with modifying function. But yang can also be dropped and one can simply say Buku merah. (The red book). So it has a silent and embedded function.

However, with a slight shift of use to colloquial Malay, the sentence Pakcik yang ‘ni ‘dok ‘kat Gelugor (The pakcik [being-this] who lives in Gelugor), finds a more difficult translation into English. The yang ‘ni in this sentence when read with ‘dok has the function of an auxiliary verb with the meaning of “he [being this] who lives”. It also denotes a physical existence of the pakcik in a temporal present. The yang ‘tu in Pakcik yang ‘tu ‘dok ‘kat Gelugor (The pakcik [being-that] who lives in Gelugor) while still assuming the function of an auxiliary verb can mean two things: the pakcik exists in visual sight but he is in a distance from the speaker; or the pakcik is not physically existent but is re-presented in the sentence as recalled memory, a shared experience (of knowing the pakcik) between speaker and listener. An article by D. van Minde, “The pragmatic function of Malay yang”, Journal of Pragmatics, Issue 40 (2008), clarified my reading and analysis. In this article, Minde seem to concur that one of the many functions of yang “follows verbs of communication, perception, cognition, verbs referring to mental processes, and performative verbs, …” (p.1995) He also acknowledged that the “inquiry of older Malay and modern Indonesian shows that yang was and is used in ways that are not fully accounted for in normative grammars and linguistic literature. What we see is the inevitable disparity between what is officially sanctioned and standardized… and what is actually going on in the language as it is used in society.” (p.1998-1999)

[4] Phenomenology is a branch of philosophy and metaphysics which emerged parallel to psychology. It proposes a knowledge or epistemology of nounema (objects) and the external world as constructed through human perception/thought, experiences and consciousness. This knowledge is not random but drawn from our understanding of the “essence” of objects in the external world. This essay generally refers to two early proponents of phenomenology: Edmund Husserl and Martin Heidegger. See Footnote [6] & [7].

[5] Semiotics is generally understood as originating from linguistics, and investigates the nature of signs and sign systems in social and material life – the inter-textual relationship of sign/signifier/signified/

[6] Dasein (Da-Sein) in German literally means “there-being”. In vernacular German, it is often used to mean “existence”. Martin Heidegger used it not as mere human existence or consciousness but in its relationship and location in temporality, or existence in time. yang ‘ni and yang ‘tu also denote being in time and space, a spatio-temporality similar to Dasein. See Footnote No. 7

[7] In Phantasie und Bildliche Vorstellung (Imagination and Visual Perception), Edmund Husserl argues that the essential difference between sense-perception and imagination lie in the different modes of human consciousness. Gegenwärtigen – an adjective which derives from Gegenwart (gegen -wart[en]), literally “towards–waiting” –primarily refers to the temporal present, but can also apply to physical presence (as in having someone present or in someone’s presence). Vergegenwärtigen, the verb, means to make present something which is not necessarily spatio-temporally present or in other words, the re-presentation of something non present through recall and memory. My analysis of yang ‘tu and yang ‘ni in Footnote No. 3 has clear parallels to these two sense-perception words in their conception of being/existence and time. Reference: Chan-Fai Cheung, Photography in Hans Rainer Sepp & Lester Embree (Eds), Handbook of Phenomenological Aesthetics (Springer: Heidelberg/London, 2010)

[8] Edmund Husserl’s epistemological arguments of knowledge claimed that we can have an objective understanding of the world not through random experiences but through “universal essences”: “What is presented to phenomenological knowledge is not just, say, the experience of jealousy or the colour red, but the universal types of essences of those things, jealousy or redness as such. To grasp any phenomenon fully is to grasp what is essential and unchanging about it.” (p.48) Martin Heidegger however argued that there are no essences are universal because we are “in the first place being-in-the-world: we are human subjects only because we are practically bound up with others and the material world, and these relations are constitutive of our life rather than accidental to it.” While this might seem materialist and historical, Heidegger notion of historicity is based on the notion of Time, not concrete Historie but rather Geschichte – what happens in time which is personally and authentically meaningful. It is an inward and existential history/time, and ultimately ahistorial. (p.57) Terry Eagleton, Literary Theory: An Introduction, (University of Minnesota:Minneapolis,2008)

[9] According to Karl Marx & Frederick Engels, the existence of human consciousness, like language, “only arises from the need, necessity, of intercourse with other men”, “and therefore, from the beginning, a social product, as long as men exist at all” (p.51). “Men can be distinguished from animals by consciousness, by religion or anything else you like. They themselves begin to distinguish themselves from animals as soon as they begin to produce their means of subsistence, a step which is conditioned by their physical organisation. By producing their means of subsistence men are indirectly producing their actual material life….The nature of individuals thus depends on the material conditions determining their production.” (p.42) Karl Marx & Frederick Engels, The German Ideology, (International Publisher Co.: New York, 2004)

[10] Conscience is commonly understood as an “inner voice” in humans. However, there are religious, secular and philosophical views about conscience. For example, in Islam, Taqwa, literally means “God-consciousness”, or a higher spiritual/moral conscience. In psychology, Sigmund Freud claims that conscience is the super-ego which represses the aggressive energies of the ego and results in guilt. Here, I use conscience from a philosophical view, mainly drawn from Hannah Arendt post-war writings: that thinking is the result of the dialogue between me and myself. By engaging in this reflexive internal dialogue, the norms and assumed axioms of thought and conduct slowly dissolve and the by-product is conscience. Conscience is directed at the self, and the externalization of this conscience emerges in the form of judgement.

~

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.

[…] This post was mentioned on Twitter by ARTERI and dill, Ralph Regula. Ralph Regula said: Ismail Hashim: yang 'tu yang 'ni (Part I) @ Arteri http://bit.ly/ehIuiH […]

Ismail Hashim’s works are among my earliest exposure to photography as art… I admire him for his ability to reframe mundane everyday scenes and bring them to the artistic level. There seems to be always a sense of quiet tension in his images….

[…] yang ‘tu yang ‘ni: Ways of Seeing and Reading Ismail Hashim’s Photographs (Part II) This is Part II of an essay written for a monograph (Penang State Museum & Art Gallery: Penang, 2010) published in conjunction with the Ismail Hisham Retrospective exhibition at Penang State Art Gallery, 2 – 30 Nov 2010. Please read Part I here. […]

any effort to bring this show in KL…National Art Gallery…perhaps

[…] Ismail Hashim: yang 'tu yang 'ni (Part I) @ Arteri […]

[…] Ismail Hashim: yang 'tu yang 'ni (Part I) @ Arteri […]