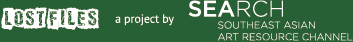

Suzanne Victor, His Mother is a Theatre (1994), Mixed Media

Classic Contemporary. I don’t think there could have been a snazzier title more befitting of a show with such ambitions. The exhibition brings together the iconic works of contemporary art within the Southeast Asian region to be consecrated as classics, complete with glamorous theatrics tailored for the idols of the new age. The curators are quite unabashed about their motivations, stating outright in the exhibition blurb that the entire building is being “transformed into a dramatic stage for these stars and icons”. Indeed, it is evident that the entire exhibition space is designed to simulate the look and feel of a pantheon for the contemporary.

Contemporary Art and History: Relocating the Originaries

Within the pantheon, everything is all sleek and edgy, but it also comes with a quaintness that we associate with the classical age, much of it coming from the dominant use of white, both in the works exhibited and the design of the gallery. The curtains, mirrors, spotlights and other embellishments also endow the works with a serene, regal austerity. In fact, the show seems insistent on drumming in the sense that we are walking on hallowed grounds.

But all the lofty airs are deliberate, for the entire show is a curatorial exercise at capturing the spirit of the contemporary via cheeky self-congratulation and a tinge of self-mockery, particularly targeting a contemporary art world that is obsessed with freeing itself from the shackles of history. Significantly, the very act of constructing a pantheon for oneself is symptomatic of a contemporary art world impatient and overzealous to bestow upon itself its own brand of antiquity, creating its own canon of Old Masters before the presentist logic of latter generations even get their chance. Canonisation is apparently no longer a task meant for the descendants.

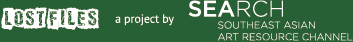

Jim Supangkat, Ken Dedes (1975), Mixed media

As expressed by the very title of the exhibition and the paradoxical image of a contemporary pantheon, the central dilemma of contemporary art is its relationship with art history. Looking at the art world today, it is evident that much of contemporary art today appears determined to derail itself from the linear narrative of art history as much as it needs to draw its legitimacy from it. Such tensions are observable in the curatorial presentation of the exhibition. By presenting iconic works of regional contemporary art as “classics”, Classic Contemporary is effectively establishing a new canon for the contemporary world, locating a new historical reference point for today’s art within the contemporary era. Such a curatorial gesture of relocating the originary is in all sense profoundly political, effectively detaching the contemporary from the trajectory of art history to create a new autonomous narrative for a strange new species of art. In fact, the whitewashed, closed confines of the gallery precisely conveys this sense of a new, insular world in its embryonic stage, at the very start of its evolutionary progression.

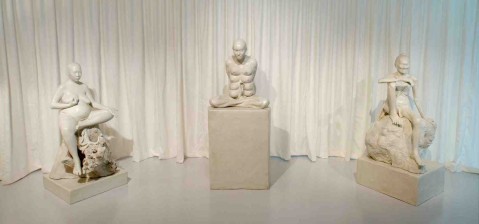

However, this brave new world ironically creates its own sense of recent history and identity by appropriating the language of the classical, revealing a critical reliance on the classical as a crutch from which it can easily derive the stable legitimacy it sorely lacks. Echoes of the medieval, classical and ancient reverberate throughout the hallowed grounds of the exhibition space. In particular, the gallery which contains works such as Jim Supangkat’s Ken Dedes and Agnes Arellano’s Three Buddha Mothers is deeply reminiscent of a classical sculpture square, particularly with the presence of white, sculptural nudes. In fact, both Supangkat’s and Arellano’s works draw their inspiration directly from antiquity, the former being a transmogrified image of a legendary Javanese queen and the latter explicitly drawing reference from the numerous trinities of goddesses within mythological history. Such observations perhaps extend what art historian Hans Belting expressed with regard to contemporary art, that it “manifests an awareness of a history of art but no longer carries it forward”. But in this instance, “awareness” would seem to downplay the significance of art history towards contemporary art world for it is through the very vocabulary of the former that the latter re-identifies and re-designates the originaries within the contemporary age. In other words, new historical reference points (at least within the regional art world) are created in the works of Suzann Victor, Redza Piyadasa or Agus Suwage by refashioning them in the language of the classical.

Timeless and Placeless in a Celestial Zenith

However, the designation of these new reference points co-exists uneasily with another characteristic of the contemporary as manifested in the show, that of a terminality of time. There seems to be very little sense of a linear progression proceeding into the distant future. Apparently, these reference points simultaneously indicate both origin and finality. Contemporary art is a species that is born into an evolutionary zenith.

Tang Da Wu, Tiger’s Whip (1991), Mixed media

Curatorially, this is made evident by the eschewing of a chronological presentation of the works. While many of the iconic works presented in the gallery are positioned as contemporary art, it must be highlighted that there are very awkward generational gaps between them. The oldest work among them, Supangkat’s piece, was made in 1975. Technically speaking, Piyadasa’s May 13, 1969 goes even farther back in history, as the exhibited piece is a remake of the 1970 original which was destroyed. In contrast, almost all of the other exhibited works were made within the last two decades, with the latest work, Handiwirman Saputra’s Cemani, Telur, Tai Kapur made just two years ago, in 2008.

Evidently, there is very little attempt to select the art works based on their representativeness of the different time periods for the logical purpose of charting any form of historical progression over the last fifty years. This would shockingly insinuate that there has probably been none. Time is apparently no longer a factor governing contemporary art but as we would soon figure out… neither is place.

On the surface, the exhibition adopts a more place-based approach as opposed to a time-based one, particularly since much attention is drawn to the places of origin and the specific cultural contexts of each represented work. But such an assertion is counterintuitive to the general sense of placelessness the works as a whole engender. As a show without a centrepiece and which treats each work as separate, indifferent equals, the denizens of the pantheon exist almost like fellow demigods who just happen to inhabit the same timeless, boundless and decentered ethereal realm. Apparently, what has happened as an extension of the flattening of the historical narrative is the flattening of spatial hierarchy and dissolution of space relationships. This is a show with neither a centrepiece nor a theoretical center from which alternative identities are formed, in a reflection of a new, decentralised art world that spans the global village. Herein lies the ambivalence: as individuals, each work is grounded by an identity ascribed by its geographical, ethnic and cultural place, but collectively, they inhabit a universe without a clear centre or any spatial markers from which an orientative sense of place can be negotiated.

Cultural Context: Contemporary Art of the Region

Evidently, the show’s greatest success is its presentation of the dilemmas of contemporary art in an intuitive, understated manner – a hallmark that distinguishes it from the more heavy-handed and aloof manner of other exhibitions with similar curatorial interests. But this fixation with the “contemporary” nature of the works does have its side effects. For one, the play with the notion of the classic, which comes with the deliberate imposition of a sense of antiquity upon the works, at times detract from their urgency and criticality as works that are a specific response to the socio-political and cultural issues of their time and place. The show becomes a little too occupied with being a fanciful academic exercise on the relationship between history and contemporaneity such that it obscures the particular nature of the works as seminal pieces of Southeast Asian art that reflect regional consciousness. Particularly given the regional identity of SAM, shouldn’t it not be the latter that merits more attention?

Perhaps it would thus be appropriate to fill in the gaps in this review, to highlight such aspects of the works which may have been overshadowed. In fact, the selection of works on display contains some of the most representative pieces of regional art that not only express the specific concerns of the region but also the cultural and institutional forces within it that transform and problematise the identity and quality of art.

[from left] Montien Boonma, The Pleasure Of Being, Crying, Dying And Eating (1993), Ceramic, cloth, bronze installation; Simryn Gill, Washed Up (1993 -1995), broken glass installationl; Vuong Van Thao, Living Fossils (2006 – 2007), Acrylic, stoneware, glaze.

There is an entire plethora of issues explored, some utterly passé (such as rote-based learning and identity politics) and others still largely relevant today (such as issues of cultural change). Despite the variety, there are distinguishing markers that exists across the collection, one of them being the recurrent fascination with the cultural artifact. This fascination is probably part of the broader obsession with the physical and the bodily, with the latter explicitly materialised in Victor’s His Mother is a Theatre. However, the cultural artifact seems to have taken on a proportionately larger prominence, moving beyond being a staple of regional art to being its signature.

While much of contemporary art from the rest of the world similarly employ the use of mundane found objects, the found objects (or their replicas) featured in the works of Southeast Asian art are typically loaded with a simulated cultural purity. They are notably often presented to appear in a largely unadulterated state. Even in the case of replicas, they are displayed like rare archeological finds so pristine, untouched and vulnerable to contamination that even an accidental brush would seem sacrilegious. The word “simulated” is used here largely because such a perceived purity is often systematically endowed rather than inherent, created either through spiritually evocative form, as seen in Montien Booma’s The Pleasure of Being, Crying, Dying and Eating, naturalistic physical arrangement, as in the case of Simryn Gill’s Washed Up or deliberate antiquation, as seen in Vuong Van Thao’s Living Fossils, in which building replicas are encased in cracked resin blocks.

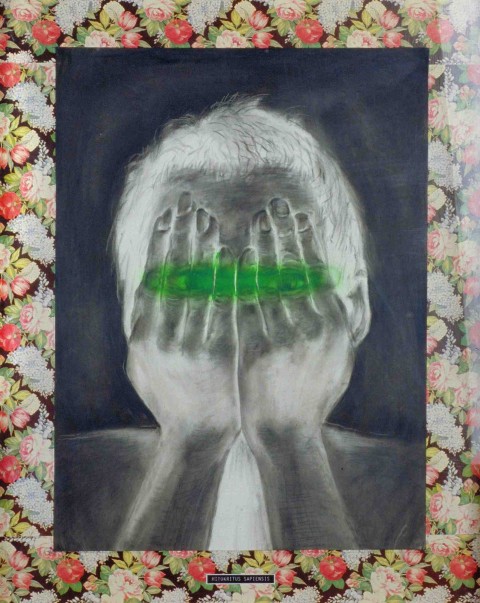

Agus Suwage, Cindera Mata A La Indonesia (Souvenir from Indonesia) (1996), Mixed media

In fact, this fixation with the pure cultural artifact is so emblematic of regional art that galleries featuring such art works appear more like anthropological museums these days! Most significantly, Suwage’s Cindera Mata A La Indonesia even explicitly appropriates the language of anthropology, with each of the quirky self-portraits titled at the bottom with a made-up Latin scientific name, such as ‘Hipokritus Sapiensis’ (Hypocritical Human) and ‘Homosapiens Sadismus’ (Sadistic Human).

This may just be a preliminary hypothesis, but it does seem to me that this penchant for employing the cultural artifact may very well arise from the growing importance of physical culture towards concretising a regional identity that has become so radically unstable. Has the homogenising potential of globalisation created a new urgency to cling onto these physical remnants as the last, visible markers of collective identity? Are the insistent efforts to lug anthropological objects into the realm of art a desperate attempt at extending their shelf life and by extension, the visibility of a diminishing culture?

Redza Piyadasa, May 13th, 1969 (2006), Acrylic on plywood and mirror

At its most simplistic, it appears as if the artist is merely participating in a process of refashioning, re-presenting cultural artifacts as works of art. This, in a way complements another distinguishing feature that similarly problematises regional contemporary art. It appears to me that many of the works presented by Classic Contemporary are also marked by a particular hastiness, as if driven by an impetus to give an immediate and unmediated reaction to a particular stimulus. In fact, it is rare to encounter a work that truly engages and exploits the properties of the artistic medium it is working within. The emphasis is instead placed on delivering a message (or lack thereof) point-blank, keeping things as literal and direct as possible. The artistic medium is no longer an apparatus for expression but a channel for delivery.

The exemplar of this would certainly be Piyadasa’s May 13, 1969, a work made in response to the 1969 Sino-Malay riots. The work is essentially an upright coffin with the Malaysian flag printed upon it. In all honesty, I don’t think that things can get any more literal than that, which is actually understandable considering that there was probably little appreciation for artistic subtlety in times of strife. However, even if the work does reflect the socio-political climate from which it emerged, chances are that it is likely to lose its evocative power and relevance over the passage of time. Our appreciation of the work today is more contingent upon our foreknowledge of its cultural context than its inherent qualities.

Agnes Arellano, Three Buddha Mothers (1996), Cold Cast marble

When there comes a work which actually bothers to engage its medium in a sensual and affecting way, the effect is often sublime. This is particularly the case for Arellano’s Three Buddha Mothers in which the soft, tactile quality of the cold cast marble imparts the monster-female hybrids with a meditative quiescence that contains a latent, potent fecundity with a capacity to (pro)create as much as to destroy. It is immediately evocative of the soft power that is often associated with such figurations of the female body in mythological iconography. The same can also be said of Victor’s epic installation, His Mother is a Theatre. While the gender politics is undeniably passé, it is hard not to be awed by the intelligent use of the installation setting to express the dual notions of presence and absence through space, motion, sound and text.

It would perhaps be fitting to end this review on a cautionary note. Despite the many arguments raised above, contemporary art, both within the region and beyond is really much more complex that what is presented by the show. After all, Classic Contemporary only features a small sample of the regional art world which is in a continual state of transformation. Nevertheless, the show is provocative on many levels. In fact, the invigorating discussion that it has stimulated is a testament to the importance of inspired curatorship in creating conversation about art. With its impressive track record despite its short history, SAM 8Q is certainly proving to be capable of taking the lead in this respect.

Classic Contemporary ran at SAM 8Q from 29 January to 2 May 2010. All works are from the Singapore Art Museum collection. Images courtesy of SAM 8Q.

~

Ho Rui An is an independent filmmaker, artist and writer from Singapore. He publishes his writings on the arts, culture and society on his weblog, http://opencontours.wordpress.com

No comments yet.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.