~

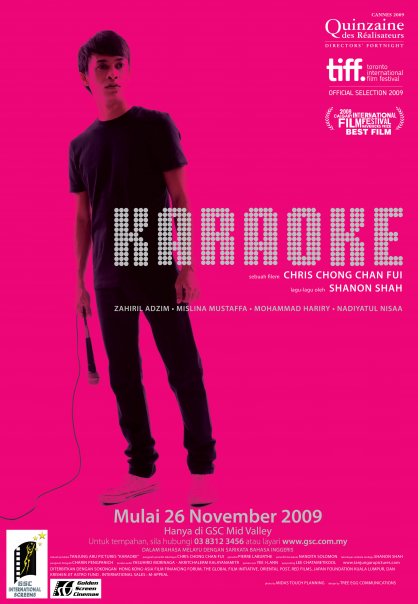

Karaoke (2009), directed by Chris Chong Chan Fui, will finally make its debut in a Malaysian cinema on November 26. Its lush visuals will be bared for public consumption after much buzz earlier this year following its acceptance into the Cannes Directors’ Fortnight.

It is exceedingly rare for Malaysian film to break into the top tiers of the global film festival circuit and Karaoke is the second to make it to Cannes and the first in 14 years. Thus, amidst the excitement and national pride there is also considerable expectation raised. Chong has already established a reputation as a skilled filmmaker with Tuesday Be My Friend (2006), Block B (2008), and Kolam (2007), which comprise two short films and a documentary, while Karaoke represents his first feature-length film.

On the surface Karaoke presents itself as a homecoming tale. The young Betik (Zahiril Adzim, atau diperkenali sebagai “Bob”), freshly graduated from a city college, returns to his village and the family business, a karaoke parlour embedded within an oil palm estate. His expectations of playing a decisive role in his widowed mother’s life are frustrated by the fact that the rest of his family have their own plans and dreams, and Betik has no clear place in them.

His mother, Kak Ina (Mislina Mustaffa), tires of the bartending life, and relations between her and his happy-go-lucky uncle, Bak (Mohammed Hariry), seem to have drawn closer since the passing of Betik’s father. Betik is slow to catch on however. In fact, Betik’s challenge seems to be that he is out of sync with those around him. Homecomings, in the tradition of Odysseus, make for poor dramatic fare if they are too easy.

Romantic prospects for the protagonist present themselves in the form of local beauty Anisah (Nadiyatul Nisaa). But Betik is clumsy in his efforts to woo her. His dreams are centred on refurbishing the karaoke parlour whereas everyone else goes to karaoke to escape the confines of their locality.

There is an Oedipal subtext to Betik’s motivations. We discover relations between he and his late father were not good. Yet he aspires to assume his father’s place and reaffirm Kak Ina’s maternal role. But there is competition from his uncle and Betik’s nostalgic attempts to connect to his father via tinkering in the latter’s toolshed leads to a diversion of his libidinal energies, shall we say, from Anisah.

Nostalgia, for some, is a cardinal intellectual sin for it “generally masquerades as rational criticism of the present and rational praise of the past”:

But nostalgia drives reasonable criticism and reasonable praise to unreasonable lengths; it converts healthy dissatisfaction into an atavistic longing for a simpler condition, for a childhood of innocence and happiness remembered in all its crystalline purity precisely because it never existed. Nostalgia is the most sophistic, most deceptive form regression can take. (Peter Gay, The Enlightenment: The Science of Freedom, [New York: Norton, 1969], p. 92)

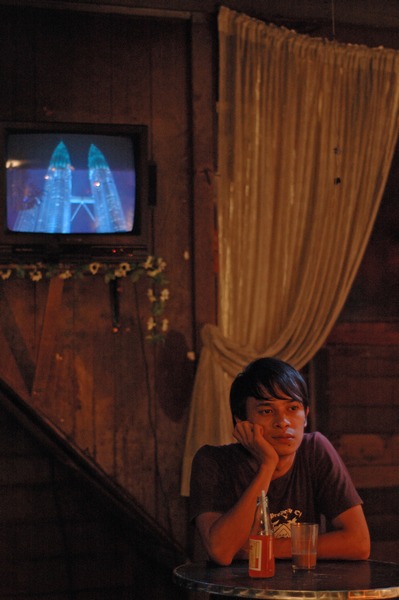

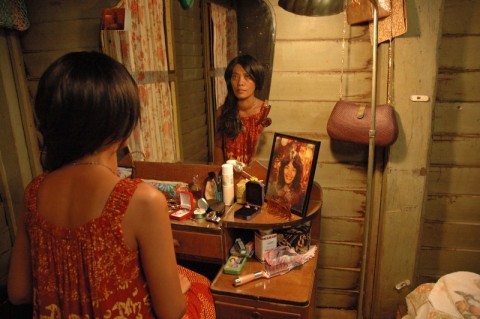

The everyday reality of Karaoke‘s characters is humdrum and mundane, as one might expect life on a plantation to be. Film typically privileges the viewer with voyeuristic access to its characters’ emotional lives. Yet in Karaoke the emotional interactions the audience is privy to are stilted, practically Victorian in their restraint. It is the karaoke songs and the pacing and content of the visuals that establish the emotional pulse of the film.

~

The Karaoke of Karaoke

Karaoke‘s script was co-written by Chong and playwright/singer/songwriter/activist/journalist Shanon Shah (of Air Con fame). While those expecting dialogue-driven character development will be disappointed, the film plays to Shanon’s strengths as a composer by interspersing the awkward interactions of the characters with catchy, humorous tunes that range the gamut from nasyid to pop. In the press screening I attended I could hear journalists in the row behind me singing along to the tunes and even humming them after the film. The staging of the karaoke songs provide for some “Yasmin Ahmad” muhibbah moments with Indian Malaysians crooning nasyid, but in contrast to the late filmmaker, Karaoke wears such moments lightly. It is not at all a pedagogical film, at least in the sense of the social mores so laboured by Yasmin Ahmad.

Finding himself unwanted and underfoot at the karaoke parlour Betik follows his uncle into the amateur karaoke video business. Eventually, he graduates from lighting assistant to lead male when the previous actor fails to show up. Thus, Betik’s dreams of karaoke parlour proprietorship shift to the practical opportunities afforded in the karaoke video business. He continues to purvey dreams and escapism, but as their avatar rather than as an entrepreneur. Rather than realising his dreams he plays out simulated fantasies for others.

The film, I think, plays with this artificiality of desire. The long, uncomfortable penultimate scene where Betik slowly and agonisingly emotes facial expressions for the karaoke video director, which we see without any score, highlights the libidinal plasticity of the consumption and production of karaoke. The formulated and formulaic fantasy of karaoke is purveyed to salve the ennui of working class plantation dwellers. It is their opiate. It is what, to whatever degree, allows them to carry on as workers within Malaysia’s plantation-industrial complex. An explicit intent of the director was to juxtapose the official denial of the artificiality of Malaysia’s palm oil-driven development (think, “We Green the Earth”) with Betik’s denial of his reality. However, even for those indisposed to palm oil-driven progress this juxtaposition can come across as too subtle to be considered a solid “take home” message of the film.

This reviewer had the chance to watch Karaoke twice, once with bloggers and an LCD projector, the second time with press on a big screen cinema. I believe it has less to do with the changes in viewing format, but I had two quite different reactions following each screening. (Disclosure: I should note at this point that several people involved in Karaoke are close friends, and I have assisted the project at different stages. Nonetheless, I am attempting an objective and critical review here.)

~

First Cut

Upon my first viewing I admired the staging, lighting, cinematography, and set production (courtesy of Yee I-Lann) as well as the catchy karaoke tunes. Karaoke features many beautifully staged shots that show off Chong’s keen sense for the visual. One such is a long static shot of a karaoke video filming on a beach. The shoreline and treeline converge on the vanishing point at screen right. The film crew slowly creep along the shore and gradually arc closer to the camera before vanishing offscreen before the viewer.

On the other hand, I found myself frustrated in trying to engage with the story through its characters. I found them emotionally limited, and yet I knew all the principals were capable actors. In post-screening discussion, the actors themselves said that they’d been instructed to perform at a “zero level”, suggesting that the film was less intended as a character drama than an experiment with formal play between the overlapping and juxtaposition of song and dialogue, video within film, narrative and visual perspective, and presumably, for the director, engaging for the first time with feature-length film.

The relationship between Betik and his mother was unclear for most of the film because there was only one brief instance of expository dialogue on this issue early on. Clearly, I blinked and missed it, which left me, like a newly arrived anthropologist, pre-occupied with trying to establish the exact nature of their kinship relation. The facts of the relationship weren’t clearly re-established until much later in the film. For much of its duration I presumed that Mislina was playing Zahiril’s older sister given that the age difference between the two actors did not appear that great.

The film was also short for a feature, clocking in at around 75 minutes, yet some scenes appeared unnecessarily long or extraneous, such as the moment where Betik’s exploration of the estate turns the film into a palm oil production documentary. One suspected that the short script produced for the film needed to be padded out to make the film long enough to qualify as a feature for the festival circuit. When the film cut to credits at the end of the first screening I found myself taken aback, as I had watched it with expectations of a character drama. I felt a number of threads had been insufficiently resolved or developed.

Had the film been longer, more like a standard feature, I felt these character issues could have been more satisfactorily fleshed out. As it was, on my first viewing, I found myself feeling that the film would have worked better as a short, especially since its pacing was slow.

~

Second Cut

I approached my second viewing with different expectations of the film. I watched it more holistically and compositionally rather than as a character-driven narrative. Consequently, I found myself enjoying it more. I diverted my expectation for emotional cues from the characters to the karaoke songs and the visual narrative.

Subjective perception of time is variable and I found the pacing satisfactory on the second view, perhaps, once again, this was due to me focusing on the visual and musical narrative rather than the character relations. But then, it occurs to me, does this make Karaoke itself a sub-species of the music video?

I mentioned earlier that Karaoke is not a pedagogical film in the socio-political sense, but I believe it presents a challenge to the way Malaysian audiences have learned to read and listen to film.

I believe the key to appreciating Chong’s particular talent is to follow the “presence” as it were, of the camera. I would suggest that it is the director-driven lens rather than the actors that is the principal protagonist of the show. The slow, languid shots which linger here or there, or meander graciously across the lusciously decayed sets. The play of colours and lights, much like a visual artist might engage with colour theory. Add to that the thematic shifts in perspective where the composition of shots and their change over time are used to drive the emotional subconscious of the narrative. The early shots of the film are tight and focused on the walled-in interiors of the parlour. Near the end of the film we are finally allowed to see the parlour in its external context surrounded by rows and rows of oil palm.

The dialogue-less mini-documentary of palm oil production becomes a soft critique of the extent of palm oil monoculture on the Malaysian landscape. Depending on one’s aesthetics, one may see this as either voracious, “greening the earth”, or matter-of-fact.

There is also clever play with the disembodied voice, text, and visual context. In one scene Chong adroitly juxtaposes the karaoke subtitles and video with what we might think at first is a conversation between two characters. Only, once the camera pans out from the karaoke video to the parlour do we see that it is instead a mental recollection of one of the conversants who sits alone, in silence.

According to some of the actors this sort of formal and textual interplay between song subtitles, scene description, and dialogue made enacting the script challenging work. Perhaps Chong and Shanon may feel it useful to release the script for consumption and dissection by critics at some point. I am sure film studies in this country could use some quality fodder.

~

Karaoke in Malaysia

Karaoke is not an “easy” film. Most Malaysians will struggle with its narrative structure and pacing as it does not pander to an audience conditioned to Hollywood or mainstream local fare. The film is a filmmaker’s film, with strong accents of European auteurship; it plays with narrative structure, story-telling methods, and features luscious cinematography. It will please those sensitive to visual composition.

It rewards repeated viewing, but it is only on local screens for one week and exclusively in MidValley’s international screen. Yes, it’s a Malaysian film, screening in Malaysia on an international screen. Odd as this might seem from the standpoint of national origin, it is a fairly honest recognition of the film’s conceptual affinities and its prospects for commercial success.

Karaoke‘s potential for achievement will be more in the realm of winning critical success and establishing that Malaysian film can compete with Euro-American films on their own terms. Whether Malaysian film should be seeking to prove itself on these terms, establishing a distinctive style, or simply making robust cinema irregardless of questions of authenticity or recognition, is open to debate. But one does not sense a critical mass of Malaysian filmmakers seeking to push this envelope or, perhaps more accurately, the existing institutions governing the financing and sanctioning of film are inimical to bolder ventures.

Meanwhile, here in the present, Karaoke is of historical significance due to the international accolades it has received and its contribution to advancing a European art-house sensibility in Malaysian film. Chong, I am aware, is generally reluctant to show his films off the big screen, so this is a rare opportunity to be seized to see both Karaoke and Block B, which will be paired twice with the former. And if you have the ringgit and time to spare, see it twice, because the visual language Karaoke tries to introduce is unlikely to be fully appreciated in a single sitting, and conceptually adventurous Malaysian film deserves to be rewarded with a strong market signal from you, its audience. And lets keep our fingers crossed for a sing-along soundtrack sometime in the near future.

~

Karaoke screens at MidValley GSC International Screen from 26 November to 2 December. Block B will be shown together with Karaoke on 28 and 29 November at the 1:30 PM screenings. ARTERI’s headquarters, Rumah MERAH, is organising a viewing expedition at 1:30 PM on Sunday, 29 November. Jom!

~

(YSL)

Production stills by Danny Lim.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.

I think it should be Oedipal, not Oepidal ;)

thanks for pointing it out, Anon! Fixed it :)

hypehypehype

Hi anon2, well deserved hype, I hope? :)

On another note, I agree with your thoughts Shao Loong. Karaoke deserves (or rather requires) more than one viewing. Simply because like any slow-paced movie, viewers struggle to grasp the general outline of the plot and the sort of structural play and pacing hinder accessibility. It is only in my second viewing, after understanding the general plot, which is a fairly simple human drama, could I then observe the delicious ways in which the drama is performed through all the wonderfully playful filmic experimentation that makes this film such a delight to watch.

Perhaps this is the film’s biggest failure, that it requires two sittings. I wonder if this is something that is worth challenging and solving for all esteemed auteurs out there.

But then again, many of my favourite films demand this of me too. Anything rewarding requires investment on my part. And perhaps this is the point where a film transcends its entertainment value.

Hope to catch this film on Thursday 26th @ GSC Mid Valley.

Simon, I’m ambivalent as to whether delivery on a single viewing is a must for film if it has artistic ambitions. Certainly, it’s a commercial practicality that needs to be honoured. But, some of the most compelling artworks reward repeated and prolonged viewing. I’m not trying to put Karaoke on a pedestal, but I think we do recognise its ambitions to experiment with visual language. I do think it would be a worthwhile challenge to find an intermediate style that could seamlessly introduce a fresh visual language such that even Hollywood-conditioned audiences could be taken along for the ride.

It was certainly an interesting film – I watched the 11.15am performance at Mid Valley.

It is a simple yet poignant tale, of the belief that things will stay static while one is away. Of course we know that not to be true, and yet we always expect it to be so.

Betik has graduated from UiTM in Graphic Design, and yet he seeks to return, finally, to his kampong, believing, evidently, that only he will have changed, moved on.

In his absence his father has died. His mother has taken up with another man and plans to sell the karaoke bar.

It is my belief that this film encompasses all those fantasies of balik kampong, for the above stated reasons.

Fantasies because ‘kampong’ while staying within us, in our longings and desires for the simpler life, exists only in a very subjective form. Frozen in time, waiting for us exactly as we left it.

But of course this isn’t so. Everything changes. The kampong we left will never stay the same, just as we change and move on so does it, and its inhabitants.

The karaoke is the same tune sung by a different singer, often badly. It doesn’t stay the same, it changes with each singer. It really is the singer, and not the song. Chris Chong Chan Fui echoes this beautifully in this simple film set in rural Malaysia.

I don’t see the Odysseus nor the Oedipus parallels. Betik is far from a returning hero, he is not cunning, not the son of royalty. He does not appear to have wanted to kill his father and marry his mother. His father is dead, true, but not by his hand.

The desire we see from Betik, is for the status quo to remain, for change not to take place, especially to his home.

Thanks for your thoughts, Yusuf. Glad you enjoyed the movie.

I wasn’t trying to draw parallels between the content of Karaoke’s narrative and that of Odysseus. I merely noted that they share the similar dramatic conceit of difficult homecomings as a story device.

Likewise with Oedipus. My gesture was to the psychoanalytic Oedipus, not the specifics of Oedipus Rex. The former concept doesn’t require a literal enactment of patricide.

Hi Shao. Yes I do understand just where you are coming from. Though I believe that the Freudian Oedipal complex is a little frayed at the edges these days, but then that is the joy of a free and open discussion – a variety of perspectives!

It’s very slow, boring and lack of CGI. I think you should refer to contemporary Hollywood movies such as Twilight, Prince of Persia, Salt, Avatar etc. Learn from the best to be the best! Better luck next time bro.

p/s – I’ll keep supporting your next film.

Yusuf – Oh yeah, the Oedipus complex was problematic from the start, though the criticisms didn’t mount until much much later. But its made its metaphoric impact on literature, lit crit, film theory, and cultural theory. And I’ve probably read too much of the latter and absorbed it. Agh!

Still, I think of Oedipality in a more generalised sense, of a “normalised” familial order, which Betik certainly seeks to restore by taking on his father’s role as protector to his mother. There are also nods to Anisah paralleling Ina, which Uncle Bak observes when he’s fitting the light. Bak nods at Betik and Ani and asks Ina if she and Betik’s father used to be like that when they were dating. A friend also observed today that Ani is Ina in reverse. Layers and layers. Intentional? We’ll have to ask the writers.

If Karaoke is shown as another feature film in a cinema, I would have gone to watch it. But sadly, as other good film works in Malaysia which go to Cannes and such are deprived (for commercial reasons, of course) from average Malaysians like me. Sigh. Tau-tau, ohh ada Malaysian film yang ditayang di Cannes. Dah tengok? Of course lah tidak.

Oh, by the way, I just knew the existence of Karaoke from Bangkok Post website (!!!) while reading a feature about Karaoke’s Thai editor.