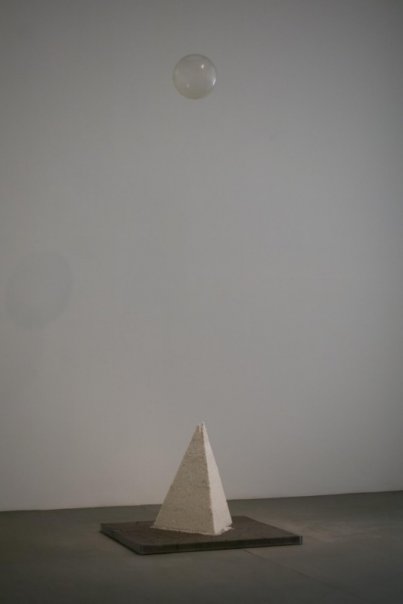

“Melting”

Nguyen Phuong Linh’s Salt

Galeri Qunyh

20 Aug – 5 Sep 2009

Galerie Quynh is situated on one of the most well-known “foreign streets” in Saigon. This is probably how one would describe the location of this gallery. Its location holds a certain charm though — not too close to the touristy area to be mistaken for a café, not too far away from the most basic activity in the everyday of the locals here – food shopping (after all, the gallery stands right in the middle of a market); so subtle and tucked-away that one can easily walk pass if they don’t pay enough attention, but mysterious and interesting enough to make them come back.

I feel the need to talk a little bit about Galerie Quynh – simply because it deserves it. This place is one of the very few galleries, or shall I say art spaces, that has been consistently dedicated and committed to Vietnamese contemporary art. The gallery’s most recent activity is the Emerging Artists Program, of which Nguyen Phuong Linh’s exhibition is a part.

I have known Phuong Linh for a year and a few months – not long enough to say that I understand her, as a close friend does. But I am confident that I am familiar and can appreciate her works, from the point of view of both an audience and a colleague. Comparing to the artist’s previous works, such as Cuntface, Button or Negative, this series of installations/sculptures in her first solo exhibition Salt shows something different – it’s a lot more matured and calmed down. It seems Linh has stopped showing her private and personal emotions, needs or wants. She is responding this time – to a world outside, a world where others’ lives and issues have become more apparent and important than her own.

Along side with a documentary and a series of photographs, the exhibition consists of four main installations/sculptures, three of which are made with salt – a material that exists in many different forms: as fluid, crystals and air. Or in other words, this natural element stands still and lives on no matter what the weather does to it – giving it a life or destroying it.

This idea somehow reflects the absurdness and harshness of the salt farmers’ lives: always watching out for the weather, pouring their blood, sweat and hearts out to protect the salt from being washed away and destroyed by the extremely unpredictable weather. On the other hand, it shows the farmers’ outstanding and courageous commitment to producing salt. Or is it to saving themselves from poverty? This then brings about a whole different set of questions – why do they keep making salt if it is too much of a problem? Because they want to? Need to? Or because that is their only chance and way of surviving?

To me, Linh’s recent art is so much more valuable and precious than those worth a ton of money, sold in galleries around Vietnam and around the world. This is art that makes us think, question and revalue what we once considered happiness, beliefs and sympathy. This is art that examines and demonstrates real life – a life outside of the pretentious and artificial gallery setting. This is art that talks back at us, and that tells the truths. And I salute Linh for having made such art.

However, as much as I admire Linh’s exploration on such themes, and her devotion and commitment to the project, I am uncertain of the way in which these ideas were transformed into real, physical artworks. The logic and link between the four installations/sculptures is rather fragile and questionable. It is very hard to see them as four separate pieces. For example, two of the works – “Flower” and “Mountains” – have the same element of repetitiveness in terms of their installation, presentation and sculptural forms. Then we have “Melting” and “Mountains”, repeating the same concern: the extreme dependence of both salt production and salt farmers on the weather. In my opinion, these two works would have worked better if they weren’t presented (or forced?) as a continuous dialogue.

On the other hand, it is also difficult to see these four pieces as a unity. For instance, although “Boat” is successful in terms of both its conceptual purposes and physical presentation, it is still the odd one out. Displaying it on its own on the first floor of the gallery only pushes the piece a bit further away from the rest. Moreover, the pod-like sculptural form represents something realistic and very close to the Vietnamese culture, while the other three – the domes and pyramid – seem a lot abstract, surreal and reflective of something more Western.

“Flower”

The work “Flower” faces the same problem. Unlike the rest, this piece is hidden away at the very back on the second floor, in a tiny space. By placing it there, the artist has eliminated any possible chance of encouraging the audience to interact with the work. We can only watch it from afar and not be able to walk in or around it. However, one can argue that that is the reason why this piece is the central and focusing point of the whole exhibition. While the rest interacts and reacts to the environment, weather and time – they will all melt into water and dissolve into air towards the end of the exhibition – “Flower” will stay the same – untouched and indestructible – just like the salt farmers themselves.

Salt exists in many different forms, as fluid, crystals and air. It has been there since the beginning of time. But without human beings, it is nothing.

~

Bill Nguyen is a fine arts graduate from Nottingham Trent University, England. He has recently returned to Hanoi and writes on contemporary art in Vietnam.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.

Cuntface…click…hmmmm…click*zoom*…GAhhrkgh

suka…