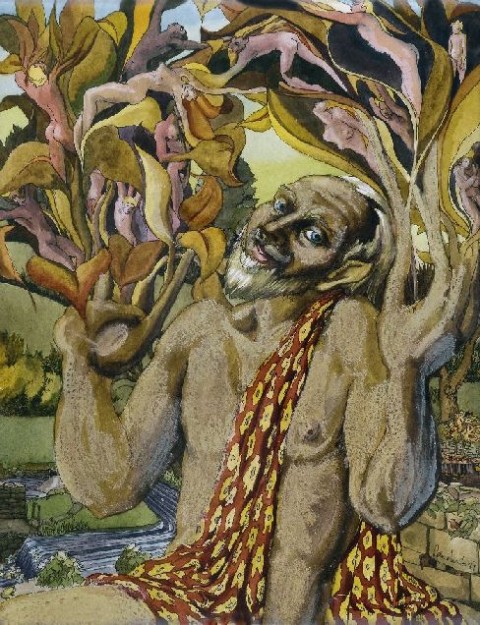

The Productive Gardener (Self-portrait), 1987, watercolour

Peter Harris (1923-2009): Once Upon A Time In Malaya

By Ooi Kok Chuen

PETER Barton Harold Harris was the pioneer of early art education in peninsular Malaysia and Sabah, and founded the influential Wednesday Art Group (WAG) which was active between 1952 to 1960.

As art superintendent in the Federation of Malaya (1951-December 1960), he was instrumental in getting potential local artists and educators scholarships to study art in Britain.

He came at a time of great socio-economic political ferment, smacked into the 1948 Emergency of communist insurgency, and on the wave of the great nationalistic excitement over a bloodless Independence handover culminating in the August 31, 1957 celebration.

In his second educational stint in the same role at the Sabah Teachers Training College (later Gaya College) from 1962 to 1967, in the then Jesselton (now Kota Kinabalu), he also got to witness the formation of Malaysia in 1963, when Sabah, Sarawak and Singapore joined although Singapore pulled out two years later to become a sovereign entity.

But he didn’t have much time or opportunity to form a WAG-style coterie of local artists during his second stint, which he blamed on the more geographically diverse terrain he had to cover.

Born in Bristol to a watchmaker-jeweller father in 1923, Harris led a chequered life with a large part of the first half of his life spent in exotic Asia as can be gleaned from his copious pastel and charcoal drawings of people wherever he went.

He first served during the war, between 1942 and 1945, in the British Air Force in Bombay (now Mumbai) and Quetta (now part of Pakistan) in India in a non-combative role as wireless mechanic with the rank of acting colonel.

He then threw himself headlong into a role more as an educationist messiah in the name of Art in what must be then frontier land on both sides of the Malaysian divide.

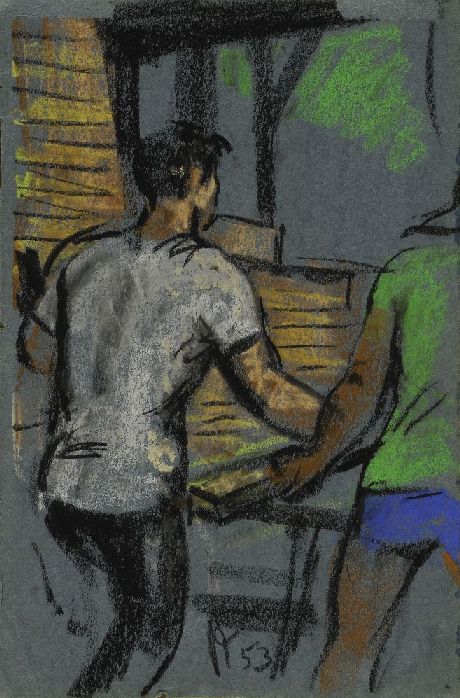

Carpenters At Work, 1953, pastel

In between, he made a rambling land-and-sea journey back to England via Thailand, Cambodia (Siem Reap to Phnom Penh), Vietnam (Ho Chi Minh City, now Saigon), before taking a boat to Hong Kong, Japan (Kyoto and Nara) and to Hawaii in the United States, before taking the luxurious Queen Elizabeth back to England.

The trip was recorded faithfully in sketches which were shown in an exhibition back home at the Royal West of England Academy and the Woodstock Gallery, off Bond Street in London.

When Harris was given a chance to return to Malaya for “doing more or less the same thing but for less pay” in Sabah, he jumped at the offer with alacrity but he was to see how different and far more backward than he imagined than the peninsular counterparts, although he relished the challenge.

After Sabah, he was inexplicably to disappear completely from the Malaysian art radar for nearly 30 years until ferreted out by artist-ceramic Yeoh Jin Leng, himself trained at Chelsea and Hornsey, for the Wednesday Art Group – Then And Now reunion exhibition held at GaleriWan in Kuala Lumpur in 1996. Even then, at 73, Harris was spritely in temperament and gait albeit with the aid of a tongkat and he was also nimble of mind, reminiscing vividly of his Malayan sojourn as if it happened only yesterday.

The conviviality and resurgent interest in WAG prompted GaleriWan to stage the Peter Harris Retrospective the next year, in 1997 (October 18 to November 1), his second – his first being given by the National Art Gallery in 1960 before he finished his first stint, the first Retrospective ever accorded by the national institution.

Harris was to hold a more substantive and extensive Tribute exhibition at patron-collector Datuk Dr Tan Chee Khuan’s The Art Gallery in Penang from January 7 to 31, 2001, in which Dr Tan also published Harris 18-page autobiography incorporated into the exhibition catalogue. It was the most important documentation of and on Harris and by Harris.

The more outstanding artists produced by the WAG were Patrick Ng Kah Onn (1932-1989), Dzulkifli Buyong (1948-2004) and Cheong Lai-tong (born 1932). Patrick Ng was to further his studies in Hammersmith and Southport (art teaching) from 1964 to 1968 and eventually settled down in England until his untimely death, Dzulkifli had an unfinished art course in Japan, while Lai-tong headed the regional advertising department of a cigarette company before re-activating his painting interests and career in a big way upon his retirement.

Other WAG stalwarts included Ho Kai Peng (TV), Ismail Mustam (advertising), Hajeedar Majid (architecture, Plymouth-trained), Datuk Mustapha Mahmud (foreign relations), Grace Selvanayagam, Renee Kraal, Sivam Selvaratnam nee Ponampalam (Stockport), Wong Siew Im (“I was his Lily Hwa, and he was my Danny Kaye,” joked Wong), Long Thien Shih, Cheong Soo Lan, Lillian Ng, Liu Siat Mooi, Phoon Poh Hoong, Syed Yahya Hashim, Yee Chin Ming, Sharaffuddin Kahar, Tushar Kanti Paul, Ahmad Hassan and later (Datuk) Syed Ahmad Jamal, who joined after his stint at the Chelsea School of Art.

Lady with Headscarf, 1966, pastel

Harris was offered the job as art superintendent of Malaya out-of-the-blue without knowing where it was and with the only instruction being that he was to pick up the local Malay language within a year.

As was the way of the halcyon days, it was the serendipity of luck, timing, naivette, daring, camaraderie and resourcefulness that got things done.

Peter Harris came into his job on the basis of his one-year diploma studies in art at the West of England College of Art in 1939 and his subsequent teaching stint at the Arts and Crafts Faculty in the College Art School in Swindon in 1947.

But the conditions in Malaya were vastly different. There was no teaching art module to speak of, art materials were scarce and amenities to say the least infrastructure were woefully lacking, and he had to face the local language (Malay) barrier and the culture shock, both ways. Skilled manpower was hard to find as there were only two who were trained at the Nanyang Academy of Fine Art in Singapore.

Because of the just-ended war, some of the primary school students had more hair than him, and they attended classes to catch up on lost time.

Peter Harris could scarcely have wished for a more comforting welcome, on landing in Penang from his long sea journey. (From there, he had to take a train journey to Kuala Lumpur although not before staying at the legendary E&O Hotel).

It was during the Emergency, declared because of the communist insurgency, and it was only a week ago that British High Commissioner Sir Henry Gurney (1898-1951) had just been assassinated near Fraser’s Hill, and imagine having to later take this same fateful route.while on the way to distribute art materials to nearby areas.

He went around giving short courses in places like Kuala Terengganu, Raub and Tanjung Malim.

He advocated an art picture gallery and an art teaching component locally instead of the more costly ritual of sending batches of students to be trained in Britain. This resulted in the establishment of the Specialists Teachers Training Institute in Cheras in Kuala Lumpur, where Harris taught briefly as a senior lecturer.

With Malaya gaining Independence, Harris’ days were numbered especially with the return of early batches of Malayan students trained in British art institutions, some of whom recommended by him.

But it was his founding of the WAG that was to prove his defining achievement of his Malayan/Malaysian tenure.

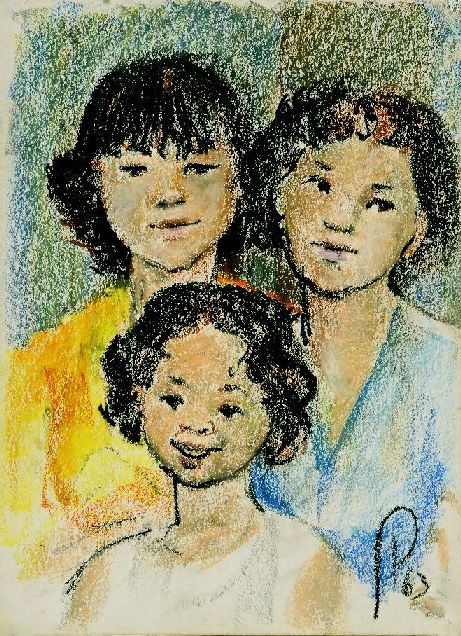

Three Sisters, 1963, pastel

Formed in 1952, the group was somehow only registered in 1956, when it started a series of successful annual shows at the British Council then headed by the arts-orientated William Emslie, who was the one who donated Patrick Ng’s Malaysian iconic painting, Spirit of Land, Water and Air to the NAG.

The sessions were first held from 6pm to 8pm, at the old barracks of Selangor Education Department near the old Sulaiman Bridge, then Dewan Tunku Abdul Rahman (now Matic), and two secondary schools in Jalan Kuantan and Bukit Bintang in Kuala Lumpur.

The WAG was another vehicle for Harris to promote art at another level, but on hindsight, it was the informal, open-ended concept that proved to be potent.

Harris told me in interviews when back in Kuala Lumpur and Penang: “I never laid down any rule. I didn’t tell them what was the right style. I only taught them the method, not the style. I can’t tell them what to paint, or how to paint it. I only forbade the use of erasers because I wanted them to know where they went wrong.”

There was also no high falutin manifesto as was wont in an age of ‘-isms’, no distinction of race, nationality, age, status, gender, class or geography, and the motley group was mostly one unschooled, enthusiastic bunch.

Besides free expressions, Harris also encouraged discussions and critical appraisals of one another’s works, but with the strict rule that there was to be no politics.

He also encouraged the students to go back to their roots, to go back to the “wonderful traditions of Chinese and Indian cultures.” Malay culture was based on the rich craft traditions and had not adopted the Western art format then.

He also said that the materials and space were free, and that they needed to pay only a RM1 fee, although soon enough most got their own materials as they became more confident in their painting.

In his peninsular stint, Harris also did charity work for children at the leprosarium in Sungai Buloh (teaching English on Sundays) and also a spina bifida centre in Jalan Ipoh in Kuala Lumpur where he basically helped paint cartoon caricatures on the ceiling and read to them. Once he and a group of artists did some sketches of towns linked by the railway line and pasted them on the walls of the school. He also ventured to Indian schools in rubber estates to help.

But there was no mention of such charity work in Sabah, where he met a different set of teacher students comprising mostly Kadazan, Murut, Bajau, Iban, Indian and Chinese. There he also met Dr Jolly Koh, who taught there for one-and-a-half years and he had also helped recommend locals like Datuk Mohd Yaman Haji Ahmad, now director of the Sabah Art Museum, for further studies.

He had no time for other things also because he was covering a wider and more inhospitable area in his work.

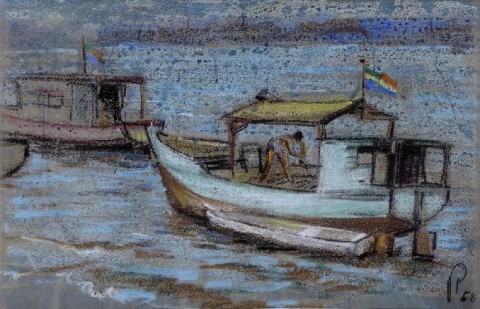

Working on the Boat, 1958, pastel

Dr Jolly Koh, who was trained in Hornsey among others and who was probably the last Malaysian artist to have seen and visited him in recent years, confided that Harris was broken by loneliness in the last five years of his life, especially after his companion died.

Melbourne-based John Lee Joo-for commented in the web eulogy that Peter Harris was regarded the White Tiger for his fulminating temper, while Datuk Tay Hooi Keat (1910-1989), who put in place a more structured art curriculum on his return from England after a stint at Camberwell (1948-1952), was dubbed the Yellow Tiger.

At his 1960 retrospective, the NAG’s working committee chairman Tan Sri Ghazalie Shafie praised Harris for “broadening the artistic vision and bringing fresh vitality to so many young Malayan artists.”

Somehow, Harris was never formally honoured for his monumental contributions to the development of early Malayan art. But in 1963, he was awarded the MBE in Buckingham Palace, London, by Queen Elizabeth II.

On his return to England, Harris went back to teaching, as a probationary teacher in a “difficult school” in Bristol before he was made the head of the Creative Arts Faculty at the Sheldon School in Chippenham in 1976.

A solo at the Malmesbury Gallery in 2000 was the only indication of some art activity during the rest of his England days.

His sketches, in charcoal and pastels, are enduring records of time, people and places. In India, there were the markets, temples, dancers, street children and old people; in Malaya, the shoe-shine boy, women with sanggul (tied as a bun at the back of the head), Chinese hand-puppet theatre, Chinese opera actors, elderly kampung folk and kampung children, racecourse scene, joget girls and even the striptease queen Rose Chan.

But it is his big works in oil and water colours that manifest his skills, techniques and philosophy. A large diptych on Mount Kinabalu – The Origin and Source (1966) and Having a Smoke (pastel), both owned by Dr Tan which he (Dr Tan) donated to the National Art Gallery and the Tuanku Fauziah Muzium and Gallery in Universiti Sains Malaysia respectively.

These, apart from five pastels and two sketches which Dr Tan also donated, to the Penang State Art Gallery in 2002.

An engaging slew of watercolours with a William Blake fantasy clinch and a surrealist slant proves to be a revelation. It is defined by The Healer (1993), which was a most therapeutic painting produced while undergoing chemotherapy for cancer in 1993. It shows three figures spreading their protective capes over a small brood of humans including a baby from the menacing threats of monsters beyond what with its gothic mock-horror landscapes.

Works of similar vein are seen in works like Tiger Lily Witch and Enchanted Garden (1995).

Harris was a flamboyant character with a caustic wit in turns. He and other expatriate pioneers like Frank Sullivan (an Australian who became a Singaporean then Malayan and then reverting to Australian, 1909-1989), Michael Moore (also early art educationist), Tan Sri Mubin Sheppard (an expert on Malay cultures who took up Malaysian citizenship) and William Willetts (an expert in Asian ceramics who died in Malaysia) belonged to an era and are known for their contributions in their respective fields.

Peter Harris died at 5.30am on March 14, 2009, at the Great Western Hospital in Swindon, England – just five weeks short of 86. His stay at the hospital was chronicled virtually realtime in a sitrep in a dedicated website, for concerned parties all over the world to be privy to his medical progress.

Peter Harris (1923-2009) Memorial Exhibition at Art Salon@SENI, Lot 55350, Changkat Duta Kiara, off Jalan Duta Kiara, Mont’ Kiara, 50480, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. info@theartgallerypg.com. Exhibition ends August 28, 2009. More of Peter’s work can be viewed here.

~

Ooi Kok Chuen is a journalist of 34 years and art writer for more than 27 years. He is awarded Australian Cultural Award in 1991, Goethe-Institut Fellowship in 1989, National Art Gallery Art Writer’s Prize in 2003 and 2008. Ooi has written more than 50 books and catalogues on art, judged several art and photography competitions, and organised art charities. He is also the project coordinator 1st Malaysia Art Tourism Expo in Malacca 2006, and deputy chairman 1st Art Expo Malaysia ‘07.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.

jadi inilah dia ‘pendidik seni’. terima kasih kerana memberitahu aku. sebelum kedatangan dia, tak ada seni di sini.

apapun aku tidak setuju dengan; “He came at a time of great socio-economic political ferment, smacked into the 1948 Emergency of communist insurgency, and on the wave of the great nationalistic excitement over a bloodless Independence handover culminating in the August 31, 1957 celebration.”

ni sejarah apa ni? sejarah siapa ni? ini bukan sejarah yg aku anuti. betul, anutan kita berbeza.

terima kasih.

did modern Malaysian art begin with dilettantism? i’m fascinated by the possibility of this attitude and approach and wonder how much it helped shape our cultural landscape.

whats ‘dilettantism’ mean? i’m looking it up…

dil⋅et⋅tant⋅ism

/ˈdɪlɪtɑnˌtɪzəm, -tæn-/

Pronunciation [dil-i-tahn-tiz-uhm,]

–noun

the practices or characteristics of a dilettante.

dil·et·tante (dĭl’ĭ-tänt’, dĭl’ĭ-tänt’, -tän’tē, -tānt’, -tān’tē)

n. pl. dil·et·tantes also dil·et·tan·ti (-tän’tē, -tān’-)

1. A dabbler in an art or a field of knowledge. See Synonyms at amateur.

2. A lover of the fine arts; a connoisseur.

adj. Superficial; amateurish.

[Italian, lover of the arts, from present participle of dilettare, to delight, from Latin dēlectāre; see delight.]

dil’et·tan’tish adj., dil’et·tan’tism n.

It required flamboyance ; ) ; )

The carpenter mmmmm

yes, rahmat haron, when ph came it was at a time of great socio-political changes in the country, whosoever’s ‘sejarah’ and which might have inhibited his plans or what he could do. that was the mileau he was thrust upon and operated from. those were the immediate post-war years, remember? and yes, simon, ph had a virtual open template when even those who put him here hadn’t a clue of what he should do. until the likes of datuk tay hooi keat put up a more structured art education system with everything else a little more settled, it was a question of hits and misses and who’s calling the shots. so what’s that word, dilettantism, or otherwise, it’s wishful thinking that our ‘modern malaysian art’ is founded on some grand systematic plans. if it looks like its origins were an afterthought, so be it.

I am trying to find information on the artist Phoon Poh Hoong.

Does anybody have any knowledge of him as i have two paintings dated 1963

Kind Regards

JM crawford

Hi JM Crawford,

I’ve contacted Arteri for your contact details unfortunately they have not come back to me. If there is any way you can provide me with your contact details, do let me know!

May have info to the artist you are looking for.

Thanks,

Sharon