by Zahirah Suhaimi

The recent controversy sparked by Chinese film, City of Life and Death by director Lu Chuan, has compelled me to mull over the challenges with establishing a universally accepted perception and use of the freedom of expression. This bold Chinese film focuses on raw human emotions during the period we know as The Rape of Nanking and has drawn considerable fire from mainland Chinese audiences. However, I believe there has been little comment from the Japanese. And why would the Japanese have anything to say when they’re solidly sticking to their version of history as misunderstood Asian liberators from colonial oppression?

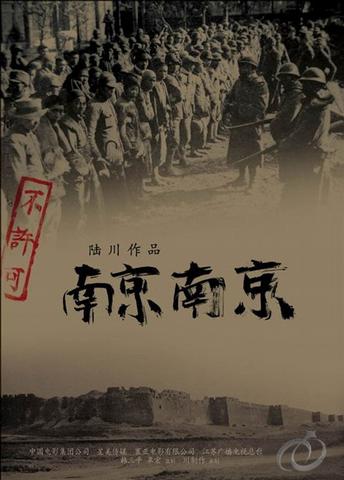

The film is similar to preceding Chinese films set in the World War II era in that it deals with the struggles of Chinese soldiers defending the motherland and the pain and suffering of the Chinese people under the Japanese Occupation. But, it also has an audacious twist – it depicts the Japanese as humans. Not that they were unearthly beings in other movies but simply characterised as inhumane, unfeeling, barbaric creatures that torture mercilessly. Giving Chinese war epic films a fresh spin, City of Life and Death paints the scene, shot in black and white, of 1937 Nanking through the narration of a Japanese soldier who, much to the chagrin of Chinese viewers, seems to possess human emotions unlike the war movies of yore. It was partly due to this film direction that audiences stormed out of theatres even before the movie ended. Others scampered out, unable to bear the intensity of emotions that were evoked by Lu Chuan’s retelling of a painful history and some still, probably could not stomach the graphic violence without which the story of Nanking would be incomplete.

Movie poster of City Of Life And Death

But before we start exiting the cinema or throwing our salted popcorn at the screens over a movie that appears to diminish the value of suffering in our history, I think we, as supposedly intelligent creatures, should realise that history, as we know it, is only one version of a possible truth. It is almost like art but instead of being a manifestation of individual expression, history is an expression of collective thoughts, emotions or beliefs with a required certain percentage of tangible evidence, depending on which entity dictates the history – which government, nation or union. The Burmese people know only what the Junta accords them in rewritten history books whilst in earlier times, Soviet history was complimentary, and never supplementary, to history as noted by the Allied nations.

So essentially, history is ‘his story’. The story of the ‘he who wins the battle’, the ‘he who writes the history books’ or ‘his own memoirs’, and ‘he with the money to make a film in order to put forward his perception of the transpired events’. Clint Eastwood helps substantiate this point with his dual-movie, Flags of Our Fathers (2006) and Letters from Iwo Jima (2006) which recreates the battle of Iwo Jima from opposite perspectives.

Between the two, I personally prefer Letters from Iwo Jima

History is also hardly her story as men have been dominant, until fairly recent times, in roles of power and politics and have thus determined who and what is to be included as historically important. Joan of Arc’s martyrdom status in the Catholic world and French history was only affirmed upon Pope Callixtus III’s, a man’s no less, decision to overturn the court’s ruling that deemed her a heretic. The very same ruling that led to her execution – burnt at the stake at the age of 19. Because it was with the assistance of the heretic, Joan, that King Charles VII attained his coronation, the Pope’s decision to dust off Joan’s crimes was thus to reinstate the legitimacy of King Charles VII. Another example would be that of Sukarno’s controversial declaration of Raden Adjeng Kartini’s birthday, 21st April, as ‘Kartini Day’ in memory of her noble nationalist contributions. Once again, we see a woman’s inclusion in history by a man in power. It is not her story as she becomes a part of his story. As we witness the emancipation of women and their roles in society, perhaps the feminist movement will not only create a feminine perspective of history but also rewrite the past and do justice to women forgotten from the pages of history, adding to the diversification, and discourse, of history.

Joan of Arc is interrogated by the Cardinal of Winchester in her prison (1824) by Paul Delaroche

Further, the presentation of history relies, to a significant extent, unfortunately, on popular news media which, more often than not, are nothing more than mouthpieces of various agendas. Thus, history is never completely objective or accommodating of every single perspective, and although it differs from art, in that the existence of art does not necessarily serve to be objective or inclusive, the opinions it chooses to express ought to be respected or perhaps even sought to be understood.

For City of Life and Death, I’d have to disagree with the Chinese viewers who find it hard to accept that Japanese people were in fact human. A difficult disposition as it puts me on opposite banks from some of the physically, emotionally and mentally wounded survivors of Nanking who find it insultingly painful to grapple with a depiction of their demonic conquerors in a kinder light. Perhaps it cannot be helped that some opinions are likely to offend certain sections of a population but as mentioned, this problem primarily arises when people are not willing to be tolerant of one’s opinions and mindful of one’s right to present a different perspective. In trying to understand the reason behind the Chinese hate for the film, I imagine it could be that pain and anger blinds, preventing them from opening up to discourse. The release of this hardly propagandstic movie, to me, is rather surprising given the widely-known Chinese government’s penchant for whitewashing anything that alters ‘accepted truths’ and even though the film went through a rigorous vetting process, having to wait 5 months for the project to be approved and another 5 for the authorities to examine it, controversial elements of the movie were left intact.

While censorship is something I’ve always stood against, believing it is what strengthens the grip of the entity I shall refer to as The Machine (or the government, if you like), I can’t help but wonder if it is something that must be employed to ensure peace and stability. Clearly, not everyone views diverse opinions as a basis or source of intellectual discourse and those that don’t, tend to be the same ones who create a state of chaos in response to ideas that provoke their beliefs. Lu Chuan’s film did not instigate violent reactions but we have witnessed how potentially explosive discourses lead to immense disruption of order and social conduct.

Gaza Strip – reaction to the Muhammad caricature by cartoonist Kurt Westergaard that was printed in numerous Danish publications, including national newspapers

Could censorship really be a noble tool to protect us from the wrath of Philistines (or was I unknowingly brainwashed after a few days back in Singapore)? Is there really a way to accommodate a diaspora of perspectives and ideologies without them impinging on each other’s right to exist?

Jakarta – response to controversial film, Fitna, by disurbingly blonde Dutch politician Geert Wilders.

Geert Wilders.

Two other epic films that I can think of, for now, that have more than raised eyebrows are A Birth of A Nation (1915), a movie based on the American Civil War where African-Americans only played minor roles that were depicted as unintelligent, sexually animalistic and uncouth and major black roles in the film were played by white actors painted black (I kid you not) and 300 (2006), where Zack Snyder’s portrayal of Persians were slammed by Iranians for being extremely and inaccurately derogatory.

Screenshot from the fim 300 of the androgynous Persian God-King, Xerxes, giving King Leonidas a massage. Ok, no. They were discussing the possibility of a Spartan surrender

When creative expression manifests into apparent discrimination, do we, or rather can we, still continue to remain tolerant of and open to it? If not, what is the basis of our selectivity and how do we create a universal criteria that balances sensitivity, and good taste, without strangling creativity?

No comments yet.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.