Why, 2008, Outside entrance to Pasar Seni LRT.

This is the unedited version of an article first published in Off the Edge Magazine, October 2008, Issue 46. Many thanks goes to OTE for granting Arteri permission to reprint.

It’s quite long so we split it into two parts.

Graffiti. Is it art or is just vandalism? Perhaps by now, after numerous articles in the popular media have posed this question some answers need to be provided. Even better, a realisation that this is actually the wrong question to ask. A more interesting one could be to consider whether or not graffiti is strong enough as an art form to function within mainstream contemporary art. Or is its recognition and respect only to be found within its own alternative sub culture?

The legality that surrounds graffiti and the invasion of public property that fuels its activity creates a much contested field of art production, since uninvited imagery on public spaces is still an illegal act of vandalism. However graffiti in Kuala Lumpur is a rich and varied visual art genre. It has its own local history, unique language, multiple styles and influences with a small, but growing, group of artists practising in the city. It is also important to understand the differences between the many types of graffiti that we see in the built environment and draw the distinction between random acts of marker tagging and technically skilled, highly considered and compositionally tight imagery.

And, although spray painting, stencilling and other unsolicited interventions in public spaces is against the law it hasn’t stopped a recognised world-wide movement bursting out of the periphery and into the mainstream. Dedicated international artists are now translating art from the street into galleries with some selling at auction for six figure price tags and exhibiting in international public museums. In addition major advertisers have commissioned graffiti artists to create visuals for their campaigns to tap into that fickle and elusive youth demographic so captivated by the genre. Therefore, audiences need to, or rather must move away from this inhibiting interpretation of an art form polarised by this question of vandalism or art, especially because graffiti so effectively reflects, challenges, and subverts popular culture with its straight talking attitude, wit and spontaneity.

Contemporary graffiti as we know it today is still a new and developing genre. Emerging over 40 years ago on New York subway cars, it has, in that short time developed into a global phenomenon with new and hybrid forms of guerrilla aesthetics appearing in the urban environment. Reasons for its appearances globally range from political protest, expressions of boredom by the disenfranchised, gangland territorial marking and art production. Understandably this has meant considerable confusion over the inclusion of graffiti into the category of Art with a capital ‘A’, especially because many individuals who practice don’t always consider themselves artists. But those who do have been included in the many umbrella terms that have appeared and disappeared in definition attempts by the art world such as graffiti art, street art, urban art and art in the built environment the latter incorporating practice with different techniques and media. However, graffiti in its purist form is about spray paint, used in a free hand technique and has many different incarnations from tagging artists names in highly stylised written characters, to wild style, throw up, blockbuster, 3-D, characters and photo realist styles. Stencils are also used to create pieces but this is considered a hybrid form. It can be isolated bursts of activity or part of long walls with contributions from many different bombers (artists who practice illegally) which can take short or long periods of time to create as well a numerous commissioned works. Graffiti has also appeared at various points in art history influencing or beginning the careers of art world giants such as Pablo Picasso, Jean Michel Basquiat, and Keith Haring and requires a practiced and controlled technique.

The history of graffiti art in Malaysia is still in its infancy and has little documentation. It began in the late 90s in Batu Pahat on abandoned and derelict buildings and then relocated to Kuala Lumpur after a few years with Bukit Bintang, Central Market and China Town being the main locus of production. There are about 30 active practitioners and 20 are considered artists with their own visual and local styles that don’t imitate international trends. Backgrounds are diverse and many artists are self taught although some have groundings in fine art and design. Categorically, all those who I was able to speak to do not consider themselves vandals or as having a need to express any political concerns or youthful rebellions but rather as artists in their own right who are very focused on the quality of their work. Although political slogans can been seen around the city competing with the pieces of the practising artists these are not connected to the graffiti artists who comment this only fuels the negative connotations associated with their practice. Graffiti art in KL is about form, colour combinations, concept and the expression of personal histories but perhaps most importantly, supporting a tightly knit community of visual artists, musicians and performers.

Like any form of highly stylised practice graffiti has its own visual and verbal vocabulary that can be unyielding in its meaning for the uninitiated. Its link to other alternative cultures such as hip hop, BMX biking and skateboarding also create invisible hierarchical boundaries for its credibility in a mainstream art world that can be elitist and unwelcoming. The appearance of graffiti in abandoned, unclaimed or temporary public spaces whether derelict buildings, construction sites, parking lot walls disturbs some audiences because of its unpredictable, uncontrollable nature and can be an unwanted presence especially when habited buildings are chosen which landlords or city councils have to pay to remove. However bombers see it as activating these otherwise forgotten, unkempt spaces to create interesting and aesthetic conversations between themselves, the public and the environment, through these ‘free exhibitions’. These conversations are taken one step further through another key goal, the desire to educate and communicate with their audiences by conducting workshops and talks with young people. Therefore could this represent an otherwise rare trait in Malaysia, albeit a subverted one, of civic consciousness? Is this process of reclaiming the forgotten and desire to educate an act of good citizenship? And surely graffiti art is a refreshing intervention and challenge to the equally invasive and globalising forces of advertising that consumes and dominates public spaces and transportation?

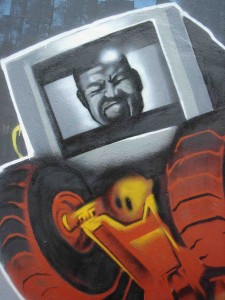

Detail from Super Sunday, 2008, Bukit Bintang

Stay tuned for part 2 tomorrow! (EM)

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.

Thanks for the information. I have a company looking into a for graffiti artists, would it be possibe if you may forward me their contacts? Thanks and keep up the good work. KL needs art.

sorry , I mean a company looking for graffiti artists.

I really like Banksy’s work which is interesting, well composed, I’m not too sure of the vandalism aspect of Graffii as I’m sure if someone for instance spraypainted your house or car I doubt you would be too happy about it. Banksy has been quoted saying “I find it very offensive when big companies have big adverts that make you feel small unless you buy their crap” which makes a really good point about the tagging of public spaces by fish big and small.

At Casula Powerhouse in Sydney they have two large water cylinders where youth can freely vandalise. I’m sure this is not a complete deterrent to vandalism but it is one way cities and councils create an outlet for creative expression.