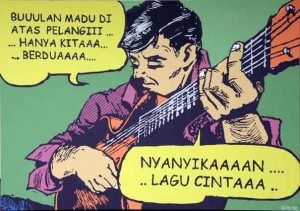

Masa-Masa Yang Indah, 2009

There is an image refusing to leave my head. It’s of a youth, guitar in hand, kampung serenading. This iconic image, for me, represents all that is Malaysian, the serenity of idyll, the incumbent artistic muse and preponderance to nostalgia.

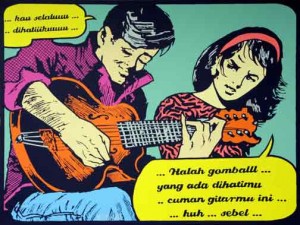

Titian Muhibah: Serumpun, Senada Seirama, by Indonesian artist Bambang Toko Witjaksono, at the Valentine Willie Fine Art (VWFA) gallery, in Bangsar, Kuala Lumpur, also offers iconographic images, essences of the muse and a hint of nostalgia by the recollection of regional TV ‘bridge building’ programmes.

On a trip to Kuala Lumpur, the artist sought ways of re-creating a dialogue between the now disparate peoples of Indonesia and Malaysia, who share a common cultural heritage. After deliberation and research, the result was those canvases which depict a time when cultural commonality was most obvious, a time captured succinctly in American influenced comic books, and now in the work of Bambang Toko.

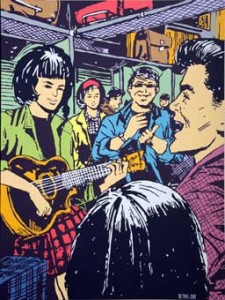

Gadis Pake Bando Yang Menarik Hati, 2009

It’s an exhibition celebrating cultural similarity and bridge building between the races of South East Asia. In its daring graphic representations and recollections it further enhances the VWFA gallery’s reputation for introducing radically diverse art forms/stunningly new art pieces to Malaysian cognoscenti, and fervent followers of contemporary art.

Upon climbing the rather steep Bangsar staircase, the bemused visitor becomes faced with the first of a series of acrylic painted canvases, depicting colourful enlarged comic book panels – some as large as 150 x 200 centimetres. The viewer becomes immersed in an Indonesian romance genre comic book, and presented with a scene of young men, one of whom stands, blue shirted, acoustic guitar in hand.

The gallery caller is subsumed into the lush pages of a graphic comic book, walking through an intensely complex narrative telling not just of the ‘low’ versus ‘high’ art snobbery and confused thinking, but through multi-layered meaning, teasing, and at times enlightening, drawing them into not just the world of contemporary art, but a world sparkling with cultural nuisances spread way beyond that of the visual representation.

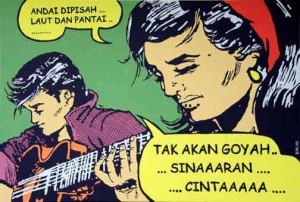

Tak Ada Yang Menghalang Rasa Cinta, 2009

Bambang Toko Witjaksono, often referred to as just Bambang Toko, creates an exhibition of acrylic paintings, based upon comic illustrations and imagery of Jan Mintaraga, doyen of Indonesian comic book artists.

Within the work, there exists undeniable art historical references to Pop Art artists like Richard Hamilton, and the use of a D.C.Comics Young Romance comic cover in his collage Just What Is It Today That Makes Homes So Appealing (1956) and, obvious reference to Pop Art guru Roy Lichtenstein, whose canvases frequently depicted enlarged scenes from comic books and advertising.

Many of Lichtenstein’s canvas images, like Drowning Girl(1963) and Shipboard Girl (1965) were taken from D.C.Comics’Girls’ Romance and Secret Hearts comic books, and, in many respects, Lichtenstein’s ‘borrowed’ imagery took secondary importance to his painting process. Lichtenstein’s work being more about a conscious representation of ‘Ben Day’ dots (the printing dots from which comic images are constructed), and the art making process itself, rather than comic book iconography.

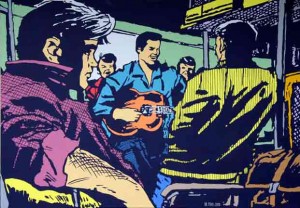

Bosan Dengan Pengamen Yang Cowok Semua, 2009

Bambang Toko’s canvases are not those of Richard Hamilton or, Roy Lichtenstein. Bambang Toko takes a step back from the stylisation of Lichtenstein’s comic book imagery, and, unlike Lichtenstein, consciously and intentionally emulates the comic book style of Indonesian romance comic books, instead of denying it.

Seemingly then it is not Bambang Toko’s intent to create just another kitsch object, nor to simply brandish the creative process, but to signify and underscore a specific social cultural nostalgia.It is, with intent and purpose, that Jan Mintaraga’s culturally relevant comic book images are chosen, and specifically those panels represented in the Valentine Willie Fine Art gallery.

While Bambang Toko presents a progression of painted canvases, depicting comic book panels, it would be remiss to claim that progression to be sequential, as in sequential art (comic art). Rather, each canvas is viewed separately, due to the visual space between the works, and not sequentially as they might be found on a comic book page. The space between the works, here, is all important for it reminds the gallery visitor that these are works of art. In their transition from page to wall, they differ in actuality, and in meaning, from the comic book images they were taken from.

For Bambang Toko, Jan Mintaraga’s comic book images appear to encapsulate the stylistic nuances of the time, conjuring an era when American comic books, and western popular culture per se, was sweeping across Indonesia, Malaysia and The Philippines.

An age innocently shared, an age uniquely enwrapped by golden webs of nostalgia and recalled by the canvases in the Valentine Willie gallery. It is an age cosily remembered with the glorious aid of retrospective illusion. A sufficiently distant epoch, into which innocence and harmony may be projected, giving the comfortable fantasy of a golden age.

Sebel, 2009

For Bambang Toko that time is the 1980s, but for the viewing audience that time could be anytime when nations are brought together. Recently Malaysia’s RTM TV station and Indonesia’s TVRI held a jointly produced programme called Ekspresi Gemilang as a continuation of the previous Senada Seirama andSenandung Serumpun TV programmes, aiming for closer musical ties between Indonesia and Malaysia.

Rather than deny his references Bambang Toko revels in them, even to the point of providing showcases in the gallery to display the original comic books and other social cultural ephemera associated with the images he has painted.

As the displayed material reveals, the exhibition Titian Muhibah: Serumpun, Senada Seirama forms part of a larger dialogue concerning accessibility of images and their cultural relevance.For, in those showcases nestle comic books, rock magazines and other cultural ephemera grounding the exhibition within its sub-cultural context.

The iconic image of the boy and his guitar, which had so haunted me, stood revealed in Bambang Toko’s exhibition Titian Muhibah: Serumpun, Senada Seirama. There it was, in its entire iconic signification, never more than a meter from my sight, a visual revelation engaging me in dialogues on art, culture, society, history and innocence, reminding me of another age’sTarik Selampit storytellers.

~

Yusuf Martin – As seen on NTV7 Malaysian national television and heard on BFM Radio; Philosophy graduate. Post Grad in Art History & Theory. Post Grad in Gallery Studies. English man living in Malaysia. Writer. Blogs at http://correspondences-martin.blogspot.com/

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.

A small thing, I know, but my name is spelt Yusuf, not Yusof.

Many thanks.

Yusuf

Hi Yusuf,

Sorry about that. I’ve corrected the mispelling! Thanks for pointing it out to us. Best wishes,

Simon Soon