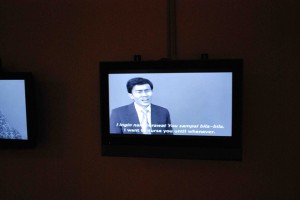

Phil Collins, dunia tak akan mendengar, 2007, video, Image Courtesy of Jakarta Biennale

Arresting in its criticality and positing of the most urgent questions surrounding art production and public engagement, ‘Arena’ the 13 Jakarta biennale is a much needed respite for jaded art tourists. Its curatorial commitment, as well as sheer production has a stirring potency for multiple audiences. And its strategy to reclaim public spaces and cultural experiences in a city with a of population of 9 million people is without a doubt, a formidable self appointed challenge. Mission statements that look at the local, regional and international through the work of artists under 40, and all with a connection to Southeast Asia makes, for once, makes perfect sense as a remit, both conceptually and in its display.

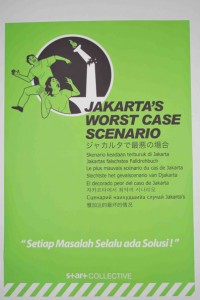

Organised by the Jakarta Arts Council and headed by Programme Director Ade Darmawaran, the remit of the 13th Jakarta biennale, focused on the city and public spaces, as an ‘arena’ for both struggle and new possibilities. The biennale programme was organised into three ‘zones’, Zone of Understanding curated by Oscar Motuloh and Farah Wardani, Battle Zone curated by Ardi Yunanto, Andy Tidjels and Irwan Ahmett, and the international exhibition programme Fluid Zone selected by Agung Hujatnikajennong. Much of the first two ‘zones’ took place in late 2008 and January 2009 and worked with local audiences and practitioners. In Zone of Understanding programmes, exhibitions and activities on literature, dance, theatre, film, photography and young people’s workshops brought public and cultural professional together. Battle Zone consisted of a public art workshop, billboard workshop and showcase of student works from the best of the Jakarta 32˚, a recurring exhibition organised by artist collective ruangrupa at the Senayan shopping mall complex. These civic engagement strategies aimed to provide what the biennale termed the ‘expansion of visual experience amongst city subjects’ and inform communities about what is going on around them.

The exceptionally curated Fluid Zone, was on display for three weeks in February this year at the National Art Gallery and up market luxury shopping mall Grand Indonesia. It consisted of recent work by artists from Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, Philippines and Thailand as well as international names who had completed residencies in the region. This was the first time selection was open to international practitioners and as such, it was an ambitious experiment to capture the zeitgeist of art production through multiple viewpoints that centred on current interpretations and questions surrounding the Southeast Asian subject.

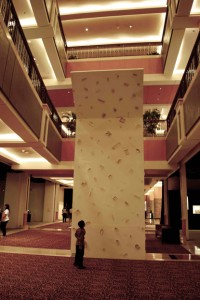

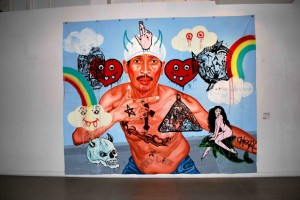

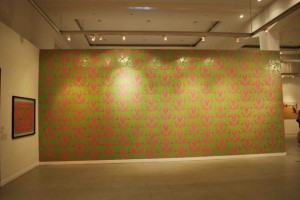

This fusion of insider/outsider gaze took on a variety of discourses and sentiments from Lyra Garcellano and Wimo Ambala Bayang’s post colonial rumblings; to playful pop culture and urban angst by Porntaweesak Rimsakul and The Secret Agent’s; Vincent Leong and Ming Wong’s take on pastiche and stereotype; as well as the gender contradictions and social commentary by Ise, Videobabes and Victoria Cattoni amongst many others. More highlights included Kuswidananto aka Jompet’s Java’s Machine: Phantasmagoria, an hallucinatory mixed media installation that looked at Javanese identity, magic and the mechanic. Phil Collin’s karaoke video dunia tak akan mendegar, of locals from Jakarta and Bandung singing songs by British band The Smiths showed the reach of international popular culture. David Grigg’s monumental paintings of gang members and commentary on life in the slums of Manila looked at fear, violence and the realities of urban life that resonate throughout the region. Poklong Anading’s Casket (Untitled), in Grand Indonesia was an homage to materialism, in the form of a white climbing wall whose hand and foots grips are plastic casts of readily discarded consumerist detritus from toothbrushes to lightbulbs. Also in Grand Indonesia, Wiyoga Muhardanto’s MPV A.K.A Multipart Vehicle, Ciao Bella and Buy One Get One Free presented subverted casts of consumer items that highlighted the absurdities and power luxury brands.

Darmawan observes the fact that neutral public spaces are diminishing and being more and more dominated by industrial and commercial forces. It is this process that transforms public space into an arena for struggle and competition. There is a need therefore, ‘to see the city as an arena to re-recognise, a place where we can devise strategies using spatial innovations and new mechanisms. We envision the city… as an arena rife with possibilities for intervention and re-negotiations among many different interests.’ He also acknowledges that everyone involved in the biennale are participants in this realm. The challenges the organisational and curatorial team faced in both production and remit, led to a very honest consideration of the chance of failure. And yet this failure rather than being an obstacle is embraced and respected as a useful tool for growth. For a biennale to openly consider its relevancy and how it can not only benefit but activate its public in such a honest and frank way in its texts and press releases is one thing. But would the actual works on display and accompanying programmes fulfil these well considered concepts? As a singular opinion, I felt that it did, and it was a much needed boost of art energy for me.

Here are my highlights. (EM)

Grand Indonesia

Donna Ong, "The Meeting", 2008, 5 single channel video projection, table,photographs and desk lamps

Donna Ong, Detail

Wiyoga Muhardanto, "MPV A.K.A Mutli-Part Vehicle", 2008, Plywood, polyester putty, motor, paint

Wiyoga Muhardanto, "Ciao Bella", 2008

Wiyoga Muhardanto, "Buy One Get One Free", 2008

Poklong Anading, "Casket (Untitled)", 2008, Clear cast resin

Porntaweesak Rimsakul, "The Story of the Teapot", Video, 2008

Galeri Nasional

David Griggs

Vincent Leong, "Tropical Paradise", 2009, aerosol spray paint with stencils

Vincent Leong, "Tropical Paradise" detail

Roslisham Ismail aka Ise, "NEP", collage, 2009

Roslisham Ismail aka Ise, detail

Ami and Popo, "Awas Begali" documentation of mural in vulnerable areas for robbery along Jalan TB Simatupang, South Jakarta

Iswanto Hartono, "Mellow", 2009, installation

Iswanto Hartono "Mellow" detail

Lyra Garcellano, "A Day in the Life of the Other", 2007, assorted toy soldiers, wooden plank

Kuswidanano A.K.A. Jompet, "Java's Machine: Phantasmagoria", 2008-09, multimedia installation

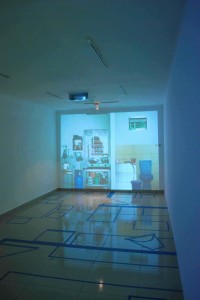

Ming Wong, "Four Malay Stories", 2005, 4 channel digital video installation

Tintin Wulia, "The (Re)Collection of Together, Stage 4, 2008, mixed media installation

Videobabes, 1:1, 2008-2009, two channel video installation

Senawan

Installation view of 32 degrees student exhibition organised by Ruangrupa and Plaza Senwan shopping mall

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.

Looks good. Love that the biennale moved into public spaces as well.

Curious, how come Jakarta can pull off something like this and KL hasn’t (yet) been able to?

In an interview with Krishen Jit, Hoy Cheong said:

“…the majority of young artists would find no awkward contradictions between rebellion and a need for the support of the dominant art institution. But I see this as a development of a parasitic culture. It is a contradiction that needs to be discussed and confronted although, at this point, I don’t know whether this tension can or needs to be resolved. You are critical of the power structures and yet you are dependent on these very powers to legitimate and evaluate the worthiness of your work.”

“You are critical of the power structures and yet you are dependent on these very powers to legitimate and evaluate the worthiness of your work.”

Holy shit. No wai. I never realised that “legitimate” could be used as a verb.

Also: nice stuff, you guys.

2 legit 2 legit 2 quit…anyone remember that one?

Wish I’d known about this earlier. Might have gone as it looks intriguing.